Source: Link

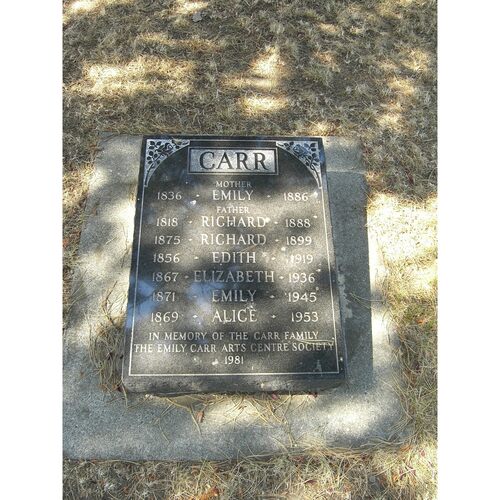

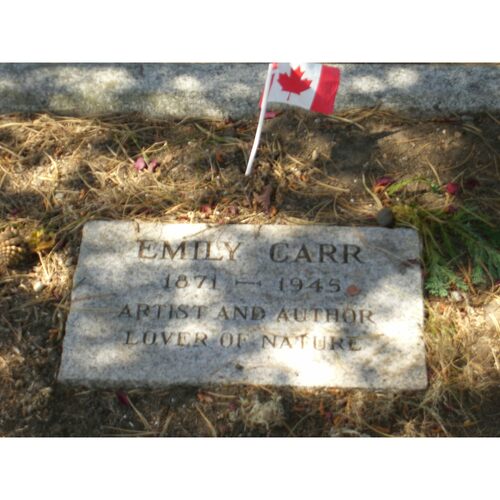

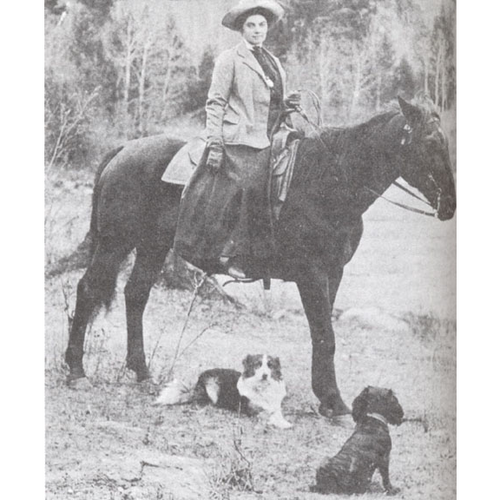

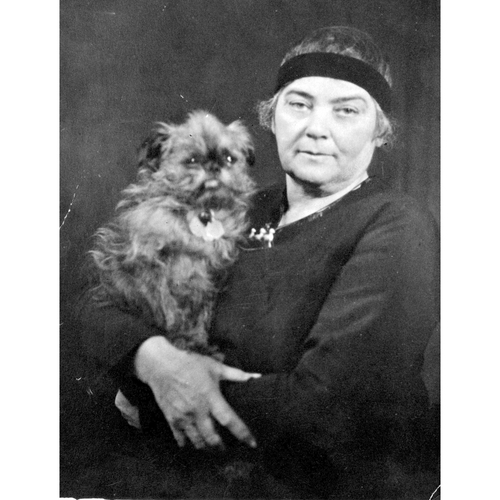

CARR, EMILY, painter, art teacher, and author; b. 13 Dec. 1871 in Victoria, daughter of Richard Carr, a wholesale merchant, and Emily Saunders; d. there unmarried 2 March 1945.

Emily Carr’s depictions of British Columbia’s coastal rainforests and the totem poles and villages of its First Nations have implanted themselves in the imagination, not only of the province’s inhabitants, but of all Canadians. The fifth child in a family of five girls (a boy was born in 1875), she showed her independence at a young age, being critical of her family’s rituals of Bible reading, prayers, and church attendance. She went to Mrs Fraser’s Private School for Children in Victoria and then to the Central Public School. In 1888 she entered Victoria High School, where she remained for less than one year. Though a poor scholar, she had demonstrated an aptitude for drawing when, at age nine, she produced a pencil sketch of her father. Encouraged by this competent, though stiff, portrait, Richard arranged for his talented daughter to receive private instruction. Emily Henrietta Woods, Eva (Evelyn) Almond Withrow, and the Misses Berry and Jorand were among the local teachers who introduced her to the romantic realist tradition of English landscape painting. The itinerant French artist Constant-Auguste de L’Aubinière and his English-born wife, Georgina Martha, née Steeple, showed Carr that art could be more than an accomplishment for young ladies. In 1890 Withrow enabled Carr to take the first step towards becoming a professional by helping her to apply to the California School of Design in San Francisco. Carr left Victoria late in the summer of 1891.

Most aspiring artists, such as Carr’s contemporary Sophia Theresa Pemberton, chose to further their training in London, England, but San Francisco was where Carr’s father had made his fortune as a merchant and had met his wife. A short boat journey from British Columbia’s capital city, it was close enough to allow Carr’s siblings to visit regularly. Above all, the California School of Design offered first-class instruction resembling that of the best institutions in Europe. Students began by drawing in charcoal from replicas of classical sculpture and progressed to the undraped model, still life, and, finally, landscape. Carr pronounced the antique and still-life classes dull. Her modesty ruled out drawing from the nude model. In her third year, she found depicting landscape a greater challenge than reproducing the well-defined contours of objects in the classroom. However, she had little opportunity to pursue this subject. Lack of funds, due to the alleged mismanagement of her father’s estate by a close friend following his death in 1888 (her mother had died two years earlier) and the economic downturn of 1893, brought Carr back to Victoria in December that year. At home – overseen by her three unmarried sisters, Edith, Elizabeth Emily, and Alice Mary – she taught art to young boys and girls. She started to exhibit her landscapes and still-life paintings at Victoria’s agricultural fair. And she found a new theme for her work.

John Webber*, who had accompanied Captain James Cook* to Yuquot on the west coast of Vancouver Island in 1778, was among the first Europeans to depict the province’s native peoples. Over 100 years later, Carr rendered the canoes and community houses of the Coast Salish on the Songhees reserve in Victoria’s inner harbour. She had read Alexander Pope’s Essay on man (London, [1733–34]), which celebrated native peoples for what he and his contemporaries perceived as their untutored minds, inherent goodness, and freedom from social conventions. It had aroused her curiosity and led her to seek contact. In 1898 she travelled to the remote Nootka (Nuu-Chah-Nulth) village of Ucluelet on Vancouver Island, where she produced pen-and-ink drawings and watercolours of village scenes, including Cedar Canim’s house, Itedsu (1898), and was given the nickname ‘T’le Wyck or Klee Wyck, meaning the one who tends to laugh.

The following year Carr journeyed to England with money saved from her teaching and she enrolled in London’s Westminster School of Art. She spent two years repeating – with the addition of painting from the nude – the courses she had taken in California. During the late summer of 1901 she fled the overcrowded classrooms and moved to St Ives, Cornwall. Working under Swedish maritime artist Julius Olsson and English landscape painter Algernon Mayow Talmage, she discovered the woods above the harbour as a motif. In the spring of 1902 she relocated to Bushey, Hertfordshire, and studied with academic landscape painter John William Whiteley. However, her classes came to an abrupt end in the autumn of 1902 because of illness or exhaustion. In January 1903 nervous strain and severe headaches, along with the guilt she experienced after rejecting her Canadian suitor William (Mayo) Paddon, resulted in her admission to the East Anglian Sanatorium, in Stoke-by-Nayland, where she remained for just over 14 months.

In old age Carr would write disparagingly of her four and a half year sojourn in England. Yet despite its drawbacks, by the time she returned to Victoria in 1904, she had reinforced her identity as a western Canadian, adopted the forest as a theme, and was equipped to begin a professional career. In 1905 she produced cartoons for the newspaper Week (Victoria). She renewed contact with native peoples during a second trip to Ucluelet, and she escaped the suffocating environment of the family household by moving to Vancouver. Over the next five years she held classes for adults and children, and she sketched the trees in Stanley Park. A regular contributor to local exhibitions, in 1908 she became a founder of the British Columbia Society of Fine Arts. She made new friends, among whom was Sophie Frank, who belonged to the Squamish community at Mission Indian Reserve 1.

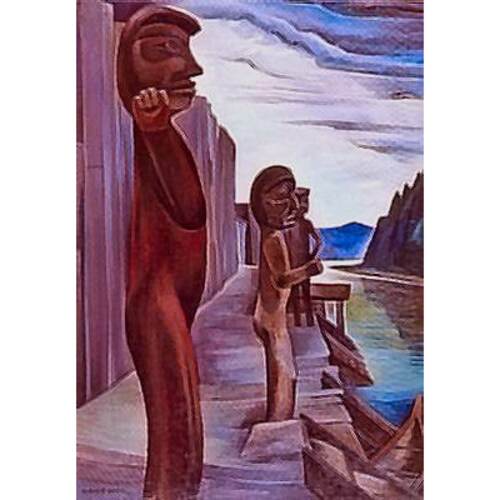

In June 1907 Carr had made a seminal trip to Alaska during which she saw its native villages as rendered by an unnamed American artist. She painted her first totem poles at Indian River Park (Sitka National Historical Park) and on her return journey reproduced poles in situ at the Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka’ wakw) village of Alert Bay. Although members of the First Nations had never stopped producing work for their own use as well as for the tourist trade, Carr, like anthropologists of the time, was convinced that she was viewing the remnants of their culture. Believing that it was her duty to document the totem poles and villages before they vanished, she spent the next three years visiting settlements on the northeast coast of Vancouver Island and in the interior of the province.

In 1910 Carr held a studio exhibition of her native-inspired canvases. The proceeds from the sales paid for a voyage to France that would last over a year. With an introduction to the Paris-based English artist Henry William Phelan Gibb and the companionship of her favourite sister, Alice, she left for Paris in July 1910. Following Gibb’s advice, she enrolled at the Académie Colarossi. Having no knowledge of French, however, she found the teachers incomprehensible. Gibb then suggested that she study with a teacher of Scottish origin, John Duncan Fergusson. She had little opportunity at that time to absorb the brilliant colours and decorative rhythms characteristic of Fergusson’s Fauve-inspired production because nervous exhaustion led to a complete breakdown. Following a slow recovery in the infirmary of the American Student Hostel, she took part in Gibb’s sketching classes in Crécy-en-Brie, east of Paris, and then in June 1911 joined him in Saint-Efflam, Brittany. The change of environment, the use of oils, the discovery that a painting could be more than a transcription of visual fact, and the act of working directly from nature prompted Carr to abandon academic conventions and embrace French Post-Impressionism, as seen in Autumn in France (1911).

After a brief spell in Paris, Carr went to the fishing port of Concarneau to study with Frances Mary Hodgkins. Like Carr, the New Zealand painter was single and a colonial; both preferred the countryside to the bustle of Paris. Hodgkins was intent on adapting her exuberant Post-Impressionist style to portrayals of the colourfully dressed Bretons around her and the Māori of her homeland. In Brittany coast (1911) Carr demonstrated that she was capable of using Hodgkins’s vivid palette, bold outline, and economy of short brushstrokes in her watercolours. When she returned to Paris six weeks later, she found that Gibb had entered two of her oil landscapes in the 1911 Salon d’Automne.

Carr returned to Victoria late in 1911 and moved back to Vancouver early in 1912. She stayed briefly with Statira Elizabeth Frame [Wells*] and no doubt influenced her art. She resumed her classes and held Friday-evening soirées. Her show on 25 March of over 70 paintings from her sojourn in France, which received a generally favourable response, introduced Fauvism to British Columbia.

Eager to apply her new style to depictions of native subjects, Carr undertook an expedition in July 1912 to the Kwakiutl, Gitksan (Gitxsan), and Haida villages along the east coast of Vancouver Island, journeyed up the Skeena River, and went on to the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii). In pieces such as Cumshewa (1912) she made the totem pole, rather than the village scene, the central motif of her Post-Impressionist-inspired work. In October she hung the canvases resulting from this trip at the Studio Club’s annual exhibition. She unsuccessfully attempted to persuade the provincial secretary and minister of education, Henry Esson Young*, that the government should acquire her collection because it documented “real art treasures of a passing race.” In April 1913 she gave lectures on native art and displayed nearly 200 examples of her paintings and drawings at Drummond Hall in Vancouver. Although the lectures and the pictures were enthusiastically reviewed, she had hoped for more sales and greater attention in the press. Already erecting an apartment house in Victoria that would provide her with a steady income, she returned to the city a few weeks later.

Carr devoted the next 14 years to running her apartment building, Hill House (the name House of All Sorts was a subsequent literary invention). She acquired a menagerie that made her the neighbourhood eccentric, took a short-story writing course, and in 1916–17 spent eight months in San Francisco. On her return she started a kennel and raised some 350 sheepdogs for sale before terminating the project in 1921. Contrary to her own later account, she did not quit painting or exhibiting during these years. In San Francisco she had helped paint decorations for the St Francis Hotel. From December 1917 to October 1919 she drew cartoons for the Western Woman’s Weekly (Vancouver). And near her home she produced canvases of the cliffs on Dallas Road that loomed above Juan de Fuca Strait. These Post-Impressionist works were shown by the Island Arts and Crafts Society, the Seattle Fine Arts Society, and the San Francisco Art Association. Nor was Carr lacking in the companionship of like-minded artists. During the 1920s Seattle-based Viola and Ambrose McCarthy Patterson and the soon-to-be-famous American Mark Tobey, who were seeking to develop a style that celebrated the uniqueness of the west-coast landscape, were frequent visitors to Hill House, as was Ina Duncan Dewar Uhthoff [Campbell*] from Victoria.

Although Carr had set aside her mission to document British Columbia’s First Nations’ peoples after she moved back to Victoria in 1913, she never lost interest in their art. Mainly for the tourist market, she made pottery and rugs that she decorated with native motifs. In 1926 she invited the Ottawa-based ethnographer Marius Barbeau* of the Victoria Memorial Museum, who was lecturing in Vancouver, to view her work; he did not accept at that time.

Carr’s meeting the following year with the director of the National Gallery of Canada changed her life. She had much in common with Eric Brown*, whom she met in September 1927. Her belief that she was painting the real British Columbia fit into Brown’s nationalist project, exemplified by his promotion of the Group of Seven. What she perceived as rejection of her work by the public in both Vancouver and Victoria and by government officials accorded with the director’s image of the struggling artist. Above all, her conviction that the native culture of the northwest coast was in decline, and that it was up to modernist non-natives to celebrate indigenous subject matter, suited the exhibition that Brown was planning with Barbeau.

In the late autumn of 1927 Carr travelled to Ottawa to attend the opening of the Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art, Native and Modern at the National Gallery. As art historian Gerta Moray has observed, Carr’s contribution to this display established her role in Canadian culture “as a mediating figure between a modern, European-dominated Canada and an exotic, primeval Native world.” During her visit to central Canada she was introduced to artists such as Margaret Kathleen (Pegi) Nicol, Annie Douglas Savage*, and members of the Group of Seven who, she felt, were “building an art worthy of our great country.” She received invitations to exhibit and made several private sales. But it was her encounter with the leader of the Group of Seven, Lawren Stewart Harris*, who introduced her to theosophy and told her how she might express her spirituality through her work, that had the most impact on the 55-year-old.

With Harris’s work and his philosophy in mind, Carr made a second major excursion, in the summer of 1928, to native villages on the Queen Charlotte Islands and along the Skeena and Nass rivers. Returning to Victoria laden with dozens of watercolours and sketches, she took a masterclass in abstraction from Tobey. When she translated her watercolours into oils such as Totem mother, Kitwancool (1928), she gave the poles greater volume and form, heightened the contrast between light and dark colours, paid close attention to the relation of adjoining rhythms, and gave the light a definite source. The following spring she contributed two paintings resulting from her northern expedition to the annual exhibition of the Ontario Society of Artists. When Harris saw her new work he assured her that her “ideas, visions, feelings were coming to precise expression.” Nevertheless, he suggested that she drop the native theme and make the province’s landscape the central motif in her art. Following his advice, she travelled in 1929 to the dense forests surrounding Yuquot.

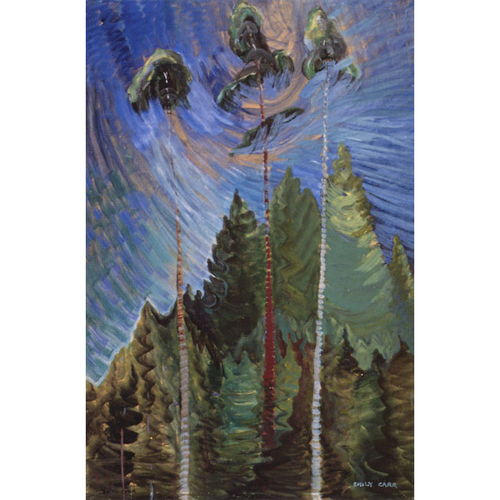

Carr had long associated the mystery and fear that she felt in the forest with the presence of God. Guided by Harris’s esoteric transcendentalism and by Tobey’s symbolist abstraction, she reduced the trees at Yuquot to cones and triangular spheres and chose a cool palette of greys and browns. Soon dissatisfied with the aloof and distant representation of God in canvases such as Grey (1929), she employed a looser, less stylized, and more expressive rendering that portrayed a more benevolent God. Lightening her palette and adapting the oil-on-paper medium for sketching, she introduced new subjects – the sea and the sky, logged-over areas, and gravel pits – that contrasted with her more enclosed depictions of the forest interior.

In 1934 Carr observed in her journal that “I am painting on my own vision now, thinking of no one else’s approach, trying to express my own reactions.” Using the full sweep of her arm, she reduced the forest vegetation in Stumps and sky (c. 1934) to a series of S-curves, chevrons, and rising spirals that caused the trees virtually to dance across the paper. From 1932 to 1936, when Carr’s Expressionist style was a vehicle for representing her spirituality, she produced some of her most accomplished paintings, including Reforestation (1936). About 1938 she completed a penetrating self-portrait. Less successfully, she brought the loosely rendered forest vegetation and the full-volume totem poles together in works that included A Skidegate pole (c. 1940).

Following her contribution to the Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art in 1927, she had made two additional trips, in 1930 and 1933, to central Canada. She renewed her contact with artists there, but also travelled in 1930 to New York, where she met and viewed the paintings of Georgia Totto O’Keeffe and visited the modernist collection of critic Katherine Sophie Dreier.

Carr’s reputation grew exponentially during the 1930s. She exhibited with the Ontario Society of Artists, the Canadian Group of Painters (of which she became a member in 1933), the Art Association of Montreal, and the Art Gallery of Toronto (her canvases accompanied those of the Group of Seven), at the National Gallery of Canada’s annual presentation, and in private galleries. In addition, her works were displayed at local shows, and they influenced emerging British Columbia artists such as Jack Leonard Shadbolt, Joseph Francis Plaskett, and Max Singleton Maynard. She continued to organize solo exhibitions, at Victoria’s Crystal Garden in 1930 and at Hill House in 1932. The Canadian National Railways’ head office in Ottawa and the Art Institute of Seattle were responsible in 1930 for the first solo exhibitions that she did not mount on her own. Solo exhibitions were also held in 1935 by the Toronto branch of the Women’s Art Association of Canada, in 1937 by the Art Gallery of Toronto, and in 1938, 1940, 1941, and 1943 by the Vancouver Art Gallery. They resulted in sales and generally favourable reviews. By the time of her death in 1945, the unflagging promotion of her work by Harris and other artists, as well as by curators, writers, and collectors based largely in central Canada, had secured her standing as a leading Canadian artist.

Sadly, by the end of the 1930s Carr had few years remaining in which she had both the financial resources and the health to exploit her great gifts. In January 1937 she suffered the first of several heart attacks. In March 1939 she would have a slight stroke. After illness prompted her in 1938 to sell the van, known as the Elephant, that had facilitated her sketching trips on the outskirts of Victoria for the past five years, she rented a series of cottages. Between 1938 and 1942 she made four excursions that provided material for Dancing sunlight (c. 1939) and less robust canvases.

After 1937 Carr devoted more time to writing in her journal, corresponding with a large circle of friends, and creating short stories. Loosely based on her encounters with First Nations peoples, her childhood, her animals, and her apartment-house tenants, her tales are sentimental and moralistic; they show prejudice against foreigners and those whites whom she considered socially inferior. They also celebrate her love of nature and her perceived closeness to the indigenous people of British Columbia. Writing courses and friends – Ruth Humphrey, a professor of English at Victoria College, and Flora Alfreda Hamilton Burns, a freelance author – had helped shape her stories since the 1920s. But it was not until 1939 that the editorial skills and publishing contacts of Canadian Broadcasting Corporation executive Ira Dilworth* gave Carr’s literary efforts a wider audience. Klee Wyck (Toronto, 1941), which received the Governor General’s Literary Award in 1942, was followed by The book of Small (Toronto, 1942) and The House of All Sorts (Toronto, 1944). Although her success as an author gave her a great deal of satisfaction, it was as an artist that she always wished to be known.

In 1942 an ailing Carr, assisted by Harris and Dilworth, set aside 45 paintings for the Emily Carr Trust she had created the previous year. The works were to be on permanent loan to the Vancouver Art Gallery. Because of concerns about a possible Japanese invasion, they were shipped to central Canada for the remaining years of the Second World War. Harris, along with Carr’s long-time friend William Arnold Newcombe, son of artefact collector Charles Frederic Newcombe*, became their trustees, while Dilworth agreed to be her literary executor. After Carr’s death Dilworth oversaw the preparation of his friend’s autobiography, Growing pains: the autobiography of Emily Carr (Toronto, 1946), and three more collections of short stories. After Dilworth’s death in 1962 his niece and heir, Phyllis Inglis, would edit Carr’s journals and publish them as Hundreds and thousands: the journals of Emily Carr (Toronto and Vancouver, 1966).

In 1945–46 the Art Gallery of Toronto and the National Gallery of Canada staged a memorial exhibition entitled Emily Carr: Her Paintings and Sketches. In 1971 the Vancouver Art Gallery marked the centenary of her birth with a major show. During the next two decades Carr’s work was celebrated in solo exhibitions and presented alongside that of other leading Canadians within the country and beyond its borders. By the early 1990s, however, her life and artistic production were being viewed in a different light. Working to a politically correct agenda, some authors claimed that she had a flawed vision of the western Canadian landscape; others felt that she had possessed a limited knowledge of native art and had appropriated native images and stories.

Despite such criticisms Emily Carr remains western Canada’s most famous non-native artist, and Canada’s leading female painter. She introduced modernism to the west coast during the second decade of the 20th century. Through her paintings and her short stories she created an awareness of First Nations culture among an initially unsympathetic, non-native audience. Above all, she provided a unique vision of the coastal landscape that made Canadians look at the forest in a new way.

Emily Carr’s personal papers and original copies of her written works are held at the B.C. Arch. in Victoria (MS-2181; MS-2763). In addition to the publications mentioned in the text, her major writings include “Modern and Indian art of the west coast,” McGill News (Montreal), 10 (1928–29), no.3, suppl.: 18–22; A little town and a little girl ([Toronto, 1951]); The heart of a peacock (Toronto, 1953); Pause: a sketch book (Toronto, 1953); and An address, intro. Ira Dilworth (Toronto, 1955).

The major collections of Carr’s art are held by the B.C. Arch. and the Vancouver Art Gallery; the remainder of her paintings and sketches can be found in galleries and private collections across Canada.

This sketch is based on the author’s Emily Carr: a biography (Toronto and Oxford, Eng., 1979). For more information about the artist and her works the reader should consult in particular the following sources: Beyond wilderness: the Group of Seven, Canadian identity and contemporary art, ed. John O’Brian and Peter White (Montreal, 2007); Paula Blanchard, The life of Emily Carr (Vancouver, 1987); Emily Carr et al., Dear Nan: letters of Emily Carr, Nan Cheney and Humphrey Toms, ed. Doreen Walker (Vancouver, 1990); Susan Crean, The Laughing One: a journey to Emily Carr (Toronto, 2001); Emily Carr: her paintings and sketches (exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Can., Ottawa, and Art Gallery of Toronto, 1945); Emily Carr: new perspectives on a Canadian icon (exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Can., 2006); Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher, Emily Carr: the untold story (Saanichton, B.C., and Seattle, Wash., 1978); Gerta Moray, Unsettling encounters: First Nations imagery in the art of Emily Carr (Vancouver and Toronto, 2006); three works of Doris Shadbolt: The art of Emily Carr (Seattle, 1979), Emily Carr (exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Can., 1990), and Emily Carr: a centennial exhibition celebrating the one hundredth anniversary of her birth (exhibition catalogue, Vancouver Art Gallery, 1971; repr. 1975); and S. K. Walker, This woman in particular: contexts for the biographical image of Emily Carr (Waterloo, Ont., 1996).

Cite This Article

Maria Tippett, “CARR, EMILY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 4, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carr_emily_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carr_emily_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Maria Tippett |

| Title of Article: | CARR, EMILY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2016 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | September 4, 2024 |