Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

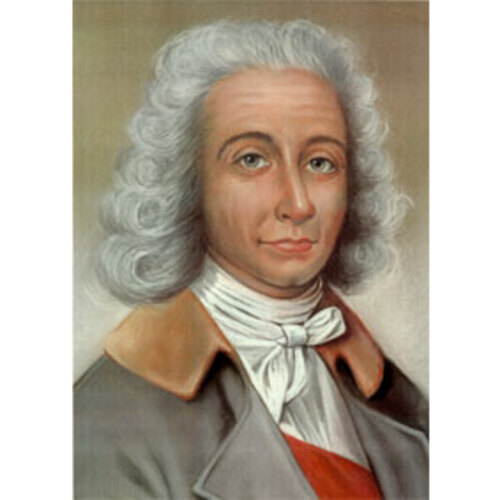

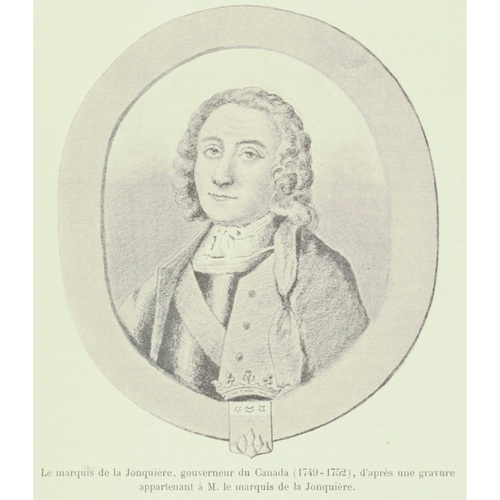

TAFFANEL DE LA JONQUIÈRE, JACQUES-PIERRE DE, Marquis de LA JONQUIÈRE, naval officer, governor general of Canada; b. 18 April 1685 at the château of Lasgraïsses near Albi, France, son of Jean de Taffanel de La Jonquière and Catherine de Bonnes; m. in 1721 Marie-Angélique de La Valette; d. 17 March 1752 in Quebec.

Jacques-Pierre de Taffanel de La Jonquière joined the service as a midshipman at Toulon on 1 Sept. 1697. He took part in his first campaigns the following year at Constantinople, then in 1699 in the Levant and in 1701 at Cadiz. In 1702 he sailed on the fireship Éclair and distinguished himself under Claude de Forbin in the operations in the Adriatic, where he commanded a sloop, then a felucca, with which he took several prizes and participated in the capture of the town of Aquileia (Italy).

On 1 Jan. 1703 he was promoted sub-lieutenant and remained in the Mediterranean. As second in command of the Galatée in 1705 he fought two privateers from Flushing (Neth.) in a five-hour battle in which his commander was killed and one of the enemy ships captured. The following year La Jonquière took part for a time in the operations conducted by the colonial regular troops against the Protestant rebels in the Cévennes mountains, then sailed on the Fendant and was on it at the siege of Barcelona, which had just gone over to Archduke Charles (the future Emperor Charles VI) against Philip V of Spain. He was given command of a small galley, the Thon, and was attacked during a patrol off Alicante (Spain) by a British ship of 60 guns, forced to surrender, and taken to England as a prisoner. He was quickly exchanged and in 1707 took command of the Galatée, on board which he had already distinguished himself, and fought two sharp actions with privateers from Flushing.

In 1708 and 1709 he sailed in the Mediterranean, and in 1710 he made a cruise to Spitzbergen. In 1711 he was commissioned first lieutenant on the Achille and took part in René Duguay-Trouin’s memorable expedition which ended in the capture and pillage of Rio de Janeiro. On 25 Nov. 1712 La Jonquière was promoted fireship captain, and the following year in command of the Baron de la Fauche he sailed to Louisiana and took part in the defence of Pensacola (Fla.). From 1715 to 1719 he waged a long campaign along the west coast of Spanish America and was named lieutenant-commander on his return to France on 20 Feb. 1720.

After six years of land service at Brest, La Jonquière received command in 1727 of the frigate Thétis, which was sent to the West Indies with the Vénus, commanded by Le Prévost Duquesnel, the future governor of Île Royale. For 18 months they made life difficult for the many pirates and smugglers who were trading clandestinely along the coasts of Martinique and Guadeloupe. La Jonquière was made a captain on 1 Oct. 1731, and in 1733 he received command of the Rubis, to escort ships to Canada. The following year he was second in command on the Éole, in the squadron commanded by Court de La Bruyère, lieutenant-general of naval forces, which was to cruise off the coasts of North Africa. In 1735 he went on station at Cadiz as commanding officer of the Ferme, and in 1738 he was again in command of the Rubis serving on the Quebec run.

When war broke out in 1739 between England and Spain as a result of many different incidents off the coasts of Spanish America, a squadron of 12 ships of the line was fitted out at Brest and sent in September 1740 to the West Indies under the orders of the Marquis d’Antin, lieutenant-general of naval forces. La Jonquière accompanied him as captain of the flagship the Dauphin Royal. Upon his return to France La Jonquière was named inspector of the colonial regular troops of the department of Rochefort on 1 May 1741. As tension with England had again worsened, a squadron of 17 ships of the line and four frigates was fitted out at Toulon in 1744 under the orders of Court de La Bruyère, who also took La Jonquière as his flag captain on the Terrible. Combined with a Spanish force of 16 ships commanded by Don Juan de Navarro, the fleet fought an indecisive battle on 24 Feb. 1744 off Cap Sicié, near Toulon, against a British squadron commanded by Admiral Thomas Mathews; then it went to cruise off the coasts of Catalonia and finally returned to Toulon. La Jonquière then commanded a division, with which he escorted convoys between Toulon and the island of Malta.

On 1 March 1746 La Jonquière was promoted rear-admiral, and on 19 March he was appointed governor general of New France. While on his way to Canada he participated, as commander of the flagship Northumberland, in the disastrous expedition led by the Duc d’Anville [La Rochefoucauld] along the coasts of Acadia, and on 30 Sept. 1746, after d’Estourmel attempted suicide, he brought what remained of the squadron back to France. Thus he was not able to go to Quebec to take up his new functions until the following year. For this voyage he was put in command of a division consisting of three frigates and two ships of the line, the 64-gun Sérieux, on which he hoisted his colours, and the 50-gun Diamant. La Jonquière left from the Île d’Aix on 10 May 1747 and four days later, at about 25 leagues west of Cape Ortegal (Spain), the convoy, which with the merchant ships and the vessels of the Compagnie des Indes comprised 39 vessels, was overtaken by a British squadron of 14 ships of the line and two frigates under the orders of Vice-Admiral George Anson and Rear-Admiral Peter Warren. It was an unequal match, since the French could line up only 312 guns against 978 for the British. Despite his overwhelming superiority Anson attacked rather uncertainly, which gave the merchant ships time to escape and to reach their destination without further interference. The ships of war lined up for battle. The combat, as bloody as it was stubborn, lasted about five hours and ended in the capture of all the French warships, which surrendered only when any possibility of resistance had gone. The Sérieux had to sustain the assault of five enemy vessels, which killed or wounded 140 of her crew and inflicted so much damage that she was in danger of capsizing with three metres of water in her hold. The Diamant was the last to surrender, after being sheared off like a hulk. La Jonquière, who had been wounded, was taken prisoner and reached Portsmouth on 28 May. The court of France then named Barrin de La Galissonière to occupy temporarily the post of governor general of New France.

When he was liberated by the peace of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748), La Jonquière was at last able to take up his post; he landed at Quebec on 14 Aug. 1749, relieving La Galissonière, who had been recalled to France. The new governor’s ideas about the colony were vague, for he had never stayed there for any length of time. On his arrival in Quebec he had some conferences with La Galissonière, and he evidently had high regard for his predecessor’s policy, since he tried to continue it in all domains, especially in relations with the Indians. In the two and a half years of his government, La Jonquière had to confront many problems, the most acute of which was obviously the defence of the colony against British encroachments in the region of Acadia and in the interior. Indeed, the peace signed at Aix-la-Chapelle had not settled any of the outstanding problems in North America over the boundaries between the British and French possessions.

During the years 1750 and 1751 commissioners from the two countries [see Barrin de La Galissonière; William Shirley] met in Paris to discuss these problems, without any particular results, while on the spot incidents were becoming more frequent, on land and on sea. The Acadians refused to recognize British sovereignty, and continuing his predecessor’s policy La Jonquière stuck to his positions, reinforced fortifications – in 1750 he had the fort on the Saint John River restored by Deschamps* de Boishébert – and in October 1751 sent the engineer Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry to France to report to the minister on the situation in that region. At the instigation of the French the Indians harassed the British unceasingly, and La Jonquière could write on 1 May 1751: “It is certain that what the Indians have done against the British at least makes up for what they have done against us.” On that same day he issued instructions “to have the Indians patrol Baie Verte continually to keep it open for us, plunder any British ship which runs aground on our territory, [and] hunt the British who are obliged to come into our territory to tow their ships that are going to Beaubassin.” La Jonquière, who wanted the Acadians to move to French territory, also ordered the Indian bands to incorporate “a few Acadians dressed and made up as Indians,” in order to compromise the white population further and to provoke violent acts of repression against them by the British, which in the governor’s mind should help decide the Acadian families to settle in French territory. In addition, in order to weaken the Acadians’ neutrality, La Jonquière did not hesitate to issue an ordinance on 12 April 1751 calling upon them to take the oath of loyalty to the king of France within a week of their arrival in French territory and to join the militia on pain of being considered rebels.

In his instructions dated 1 April 1746 La Jonquière had been advised to keep an eye on British intrigues among the Indians at Sault-Saint-Louis (Caughnawaga, Que.), and to endeavour to destroy the British post at Fort Oswego (Chouaguen), on the south shore of Lake Ontario, which constituted an active smuggling base. The governor general’s policy towards the Indian tribes vacillated, however, and he was not successful in using them effectively in the struggle against the British. Fort Rouillé (Toronto) was built in 1750 to compete with Oswego; the post at Detroit was reinforced because of its economic and military importance, and an ordinance on 2 Jan. 1750 accorded numerous advantages to families willing to settle there. But in the Ohio region he failed completely. Posts were improved below the portage at Niagara and at Sault Ste Marie near Lake Superior, but the governor’s visit in 1751 to the Iroquois at Sault-Saint-Louis and at Lac des Deux-Montagnes, who received him well with military honours, was of little importance in the struggle against British expansion. In June 1751 Philippe-Thomas Chabert de Joncaire was sent to the Six Nations to renew the peace treaties concluded in the time of their ancestors with Governor Callière*, and François Lefebvre Duplessis Faber negotiated with the Ottawas and endeavoured to prevent them from trading with the English. In addition, through an ordinance issued on 27 Feb. 1751 La Jonquière had authorized Ensign Pierre-Marie Raimbeau de Simblin to establish a fort at Lac de la Carpe to counter British influence in the area south of Hudson Bay. The mission to the Sioux which the governor entrusted to Paul Marin de La Malgue was aimed at restoring peace between them and the Missouris.

The governor general, who in most cases seems to have been well served by his officers, had great difficulties with Pierre-Joseph Céloron de Blainville who, according to the governor, showed obvious ill will in carrying out orders concerning the campaign against the Indians of Rivière à la Roche (Great Miami River, Ohio). But La Jonquière had given him only a small number of troops from Canada and Céloron was not able to recruit Indians “because of the small number of Frenchmen . . . who have arrived from Montreal for this expedition.” La Jonquière had to send François-Marie Picoté* de Belestre to investigate; Belestre went to France at the end of 1751 to report to the minister. The governor also had a rather sharp dispute with the Jesuits over the Sault-Saint-Louis mission and the missionary Jean-Baptiste Tournois. Three persons from Montreal, Marie-Madeleine, Marie-Anne, and Marguerite Desauniers, had set up in business at the mission around 1726 and were actively engaged in trade, sometimes illicit. La Jonquière expelled them from the colony, as well as Father Tournois, who was suspected of having aided them.

Trade with the pays d’en haut, on which two ordinances were published on 29 May 1750, aroused many complaints from certain traders, who claimed that the fur trade was monopolized by “a private company formed of a small number of persons, including officers of the trading posts.” La Jonquière, who at times seems to have exhibited a certain naïvety, weakly defended the persons concerned, prudently adding: “There is no one in this country who is not secretly motivated by self-interest.” The governor general himself was not free of it and let himself be drawn by Intendant Bigot* into commercial speculation from which his position should have forced him to abstain. Despite the court’s prohibition, he entered into partnership with Bigot, Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, and Paul Marin de La Malgue to operate the postes de l’Ouest and the post at Baie-des-Puants (Green Bay, Wis.), and allowed his secretary, André Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, to proceed freely with his embezzlements. The stir caused by the Tournois-Desauniers affair and the denunciations and complaints sent to Versailles were, in fact, on the point of causing La Jonquière’s recall when he died. Exactly what was his role in Bigot’s Grande Société? It is difficult to determine precisely. Above all it seems that he allowed profits to be made and collected some himself, without playing any role personally in commercial operations.

To meet the British threat the governor general concerned himself with increasing the military forces of the colony. He asked for and obtained the dispatch of recruits whom he mixed in with the experienced soldiers to bring company strengths up to 50; he created a company of gunners, which was raised in 1750, and he went ahead that same year with a general census of the militia, which included about 12,000 men. La Jonquière would have liked to see the post of general officer commanding the troops and militia re-established, and he counted above all for the defence of the country on the Canadians, because the soldiers from France “not being trained since their early youth in getting about in the pays d’ en haut, still less in Indian warfare, are good only for garrisoning towns.” New barracks were built in Montreal and Quebec; work also went on to fortify Quebec, despite opposition from Versailles, which feared that it would attract an attack by the British. A meeting of the inhabitants called by Charles de Beauharnois and Gilles Hocquart* after the capture of Louisbourg in 1745 had decided on the necessity of fortifying the town, and La Jonquière was not able to oppose the carrying out of this desire.

Peopling the colony worried him, and like his predecessor he would have liked to attract new settlers. “Men are extremely scarce,” he wrote the minister on 6 Oct. 1749, “and the war has carried off many of them. The majority have gone to France or the West Indies, where they have remained, and we can only replace them by discharging men from the troops to get married.”

As a good sailor La Jonquière concerned himself with improving piloting on the St Lawrence and also wanted to encourage shipbuilding at Quebec. Unfortunately, as a result, it seems, of an error on the part of the builder, René-Nicolas Levasseur*, the ship Orignal broke up on the day it was launched and could not be repaired. This accident did not, however, prevent the Algonkin from being laid down.

Among the projects which the governor general did not have time to carry out was the creating of a printing house in the colony, which he proposed in October 1751, and the reform of the administration of the Hôpital Général of Montreal, which an ordinance of 15 Oct. 1750 joined with that of Quebec to receive all the old and disabled in Canada and Île Royale. Because of its unrealistic nature this decision, ordered by the minister, provoked vigorous protests, and was not carried out [see Marie-Marguerite Dufrost* de Lajemmerais].

La Jonquière proved to be a good administrator in Canada but hesitant in a time of political and economic difficulties. He was certainly a man of great courage, and his naval career, comprised of 29 campaigns and nine combats, is proof of that. It is certain, however, that he liked money and turned out to be regrettably greedy. He was able to see clearly certain problems facing the colony and succeeded partly in following his predecessors’ policy, but he lacked firmness in his dealings with the British and the western Indians and showed unpardonable weakness, particularly in his relations with Bigot. Shortly after his death, which occurred on 17 March 1752 after some months of illness, the acting governor, Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil, and Intendant Bigot could write: “We have missed him very much.” These regrets seem to have been shared by the population.

AN, Col., B, 89–95; C11A, 95–97; F3, 69, ff.218ff.; Marine, B1, 63–64; B2, 269, f.33; 324, ff.466, 519; B3, 289, ff.256–57; 312, ff.34–41; 315, f.322; 426, ff.449–530; 446, passim; B4, 61, ff.101–75; B8, 28, ff.693, 822, 851; C1, 165; 166, p.21. Étienne Taillemite, Dictionnaire de la marine (Paris, 1962), 162. Frégault, François Bigot; Le grand marquis; La guerre de la conquête. Lacour-Gayet, La marine militaire sous Louis XV (1910). Troude, Batailles navales de la France, I, 311–15.

Cite This Article

Étienne Taillemite, “TAFFANEL DE LA JONQUIÈRE, JACQUES-PIERRE DE, Marquis de LA JONQUIÈRE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/taffanel_de_la_jonquiere_jacques_pierre_de_3E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/taffanel_de_la_jonquiere_jacques_pierre_de_3E.html |

| Author of Article: | Étienne Taillemite |

| Title of Article: | TAFFANEL DE LA JONQUIÈRE, JACQUES-PIERRE DE, Marquis de LA JONQUIÈRE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1974 |

| Year of revision: | 1974 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |