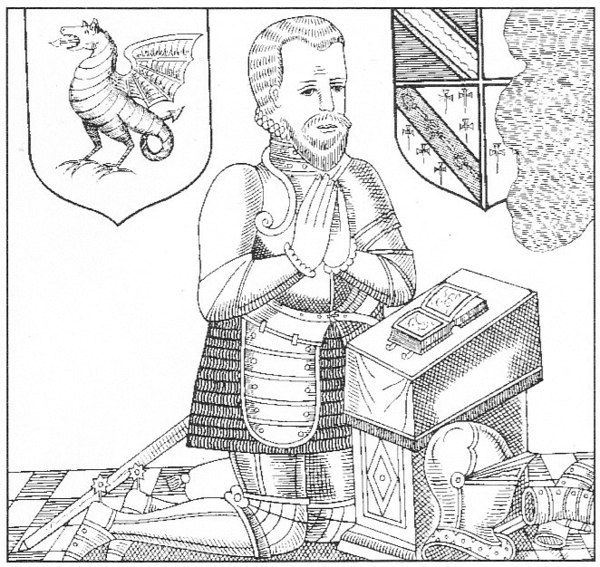

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DRAKE, Sir BERNARD, commander of an English expedition to Newfoundland; b. c. 1537, d. 10 April 1586.

He succeeded his father in 1558 as head of the Drake family of Ashe, Musbury, Devon, and occupied himself in building up his estates and in local government. He was a first cousin of Sir Richard Grenville and may have been distantly related to Sir Francis Drake. He married Gertrude Fortescue and had several children.

Bernard was first attracted to American ventures by Sir Humphrey Gilbert in 1582 and he undertook to lead a party of adventurers to settle whatever part of North America Gilbert had sold him on paper. However, he did not go or participate in any overseas ventures, so far as is known, until 1585, when he agreed to take part under Sir Walter Raleigh in the venture for planting Virginia. He was to lead a second squadron through the West Indies, with its chance of Spanish prizes, to Roanoke Island (modern North Carolina) where a colony was to be settled by Sir Richard Grenville, who had left Plymouth in April. Drake’s ship, in which Amyas Preston – a gentleman of Cricket, Somerset, who was afterwards to be a prominent privateer and naval commander – had a share, was the 110-ton Golden Riall of Topsham, where Bernard Drake had a house. With her was associated Sir Walter Raleigh’s Job, 70 tons, Capt. Andrew Fulford, and apparently a vessel commanded by Hugh Drake, perhaps the pinnace Good Companion. There were others too among the “divers good Ships under his command” which Richard Whitbourne saw at Newfoundland, possibly one large and two smaller, of which we have no details.

On 26 May the Spaniards clapped an embargo on English shipping in Bilbao harbour, as they were doing all over Spain; the ship Primrose fought her way clear and brought the news to London. There it was decided to release a large number of privateers in reprisal and to take precautions against other merchant ships’ being caught in Spain. On 10 June Raleigh was authorized to impress ships for a voyage to be made to Newfoundland so as to warn English fishing vessels there not to take fish direct to Spain or Portugal (the triangular trade being already well established), and to seize any vessels belonging to subjects of the king of Spain they could find. Commissions to lead such expeditions were issued to Carew Raleigh and to Bernard Drake on 20 June, and the latter was ordered about 27 June to abandon his Virginia voyage and take himself off to Newfoundland; Carew Raleigh apparently remained at home.

Drake probably set out early in July and reached Newfoundland by the end of the month, though we have no precise dates for the voyage. On the way over, the Golden Riall, perhaps with her pinnace, sailed far enough south to capture a rich, sugar-laden Brazilman. This valuable Portuguese prize was put in charge of Amyas Preston and was sent home, duly arriving at Exmouth, while Bernard Drake went on his way. In the absence of a narrative of the voyage we cannot say precisely how Drake made contact with his other ships, but he probably encountered them only at a rendezvous at St. John’s, the obvious first port of call for the performance of his dual mission. It would have been here that Whitbourne saw him. After warning the English fishing captains and impounding enemy shipping there, he is likely to have dispersed his squadron, in convenient groups, to the other harbours which the English fishermen frequented.

Though the episode is usually characterized as the seizure of the Spanish fishing fleet, Drake did not, and was unlikely to, meet with more than an occasional fishing vessel, as the Spanish fishery was based on the southwest and west shores of Newfoundland, while the Portuguese shared harbours with the English in the southeast and east, and had already in 1582 suffered from English anti-Spanish reprisals following on the Spanish conquest of Portugal in 1580 [see Clarke]. Bernard Drake himself took the Golden Riall south to Bay Bulls where he encountered George Raymond in command of the Red Lion of Chichester, 100 tons. Raymond was from Chichester, Sussex, and had sailed with Grenville to Virginia in April and landed his quota of colonists at Croatoan on the Carolina Outer Banks in June, before coming on to Newfoundland, where, it is not unlikely, he was already looking for Portuguese prizes. Drake joined forces with him and together they made more captures.

Leaving their consorts and prizes to make their own way home the two commanders sailed to the Azores where they were highly successful in prize-taking, overpowering a straggler from the homeward-bound Spanish West Indies fleet, which had some wine and ivory on board (though we do not know what its main cargo was), and no less than three Portuguese Brazilmen all laden with sugar. Another prize was a ship of La Rochelle from Guinea with a little gold. (Though brought to England she was later restored to her owners as she may have been under charter to English merchants.) We have no precise inventory of the Portuguese fishing vessels taken, but they totalled 16 or 17 in all. Some did not reach England. Their captors met with very bad weather and anything from two to seven of them may have been lost at sea, while the Lion of Viana, 180 tons, with Thomas Raynsforde as captain of her prize crew, along with Raleigh’s Job, were forced into Breton ports and held captive there. Raymond brought a Brazilman to Chichester and some fishing vessels to the same port and to Portsmouth; the other two Brazilmen and the Spaniard followed Preston’s prize into Exmouth, while by mid-October 600 Portuguese fishermen were scattered with their vessels amongst other southwestern ports.

The total haul of 21 or 22 vessels represented an appreciable victory for the English. The Brazilmen and the Westindiaman were worth at least £10,000 and the fishing vessels perhaps as much again, though values up to £60,000 were mentioned, and it is likely that much spoil went clandestinely to the seamen. Profits were high, as the initial cost of the expedition was about £3,500. The government, not to be robbed of customs duties and the lord high admiral’s share, appointed commissioners in Devon, Somerset, and Dorset to appraise the prizes and distribute the proceeds, allowing the captives 3d. a day maintenance until repatriated. Raleigh and Sir John Gilbert appear to have had a major say in the final division, though particulars of it have not survived, except that four of the five most valuable prizes went to Bernard Drake and his son, though they withheld Amyas Preston’s share in the one he brought home. This, Sir John Gilbert was finally ordered by the Privy Council to repay in 1589, as he had handed the vessel to the Drakes.

Bernard Drake had the crew of one of the Portuguese vessels brought to Dartmouth imprisoned in Exeter: the charge must have been a criminal one (mutiny perhaps). He made them no allowance and they starved through the winter except for some charity shown them by the citizens. He himself went to London where, at Greenwich on 9 Jan. 1585/86, Queen Elizabeth knighted him in recognition of his success. The Exeter assizes opened on 14 March. The chief justice of common pleas, Sir Edmund Anderson, who was on circuit, when he learnt of the plight of the 38 prisoners – all now seriously ill – reprimanded those responsible for their malnutrition and Drake in particular. The trial judge was Baron Flowerdew and he had with him on the bench a group of local justices of the peace, including Sir Bernard Drake. There was a great stench when the prisoners were brought to the bar and it is not known that any sentence was passed on them, but within a little more than three weeks the judge, 8 J.P.s and 11 of 12 jurors, with some of the court officials, were all dead of an infection caught from the Portuguese. Sir Bernard Drake, when he fell ill, struggled as far as Crediton on his way home but died there on 10 April and was buried two days later. An epidemic of what was apparently typhus raged in Devonshire for more than a year. If it was entirely the consequence of the Newfoundland raid, which is not established, the cost of the latter in loss of life was very great. John, Drake’s eldest son, succeeded to the estate of Ashe and to the family’s new and old wealth.

BM, Lansdowne MS 148, ff.127–28. PRO, H.C.A. 14/23, nos. 164(a-b)–165; C.142/211/175; S.O.3, Ind. 6800; S.P.12/144, no.59; 12/179, nos.1–2; 12/183, no.13; 12/185, no.60; 12/186, no.8; Acts of P.C., 1588–89, 383–84; CSP, Spain, 1580–86, 535. R. Holinshed, Chronicles, ed. H. Ellis (3d ed., 6v., London, 1807–8), IV, 868–69.

C. Creighton, History of epidemics in Britain (2v., Cambridge, 1891). DNB [see articles on Sir Bernard Drake, Edward Flowerdew, Sir Amyas de Preston].

English privateering voyages to the West Indies 1588–95, ed. K. R. Andrews (Hakluyt Soc., 2d ser., CXI, 1959) [for George Raymond and Amyas Preston]. Roanoke voyages (Quinn), I, 171–73, 234–42. A. L. Rowse, The England of Elizabeth (London, 1950). The visitations of the County of Devon, comprising the herald’s visitations of 1531, 1564 and 1620, ed. J. L. Vivian (Exeter, [1895]). Voyages of Gilbert (Quinn), I, 61, 95; II, 333.

Cite This Article

David B. Quinn, “DRAKE, Sir BERNARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drake_bernard_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drake_bernard_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | David B. Quinn |

| Title of Article: | DRAKE, Sir BERNARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |