Source: Link

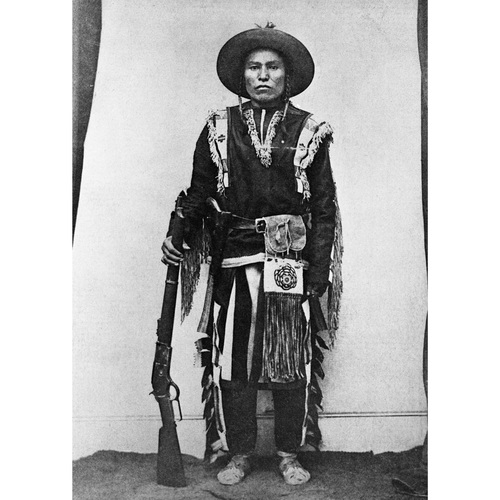

KUKATOSI-POKA (Starchild, sometimes referred to as Kucka-toosinah), Blood Indian and NWMP scout; b. c. 1860, probably in what is now southern Alberta; d. in December 1889 on the Blood Indian Reservation (Alta).

Little is known of Starchild’s early life. He was about 14 years old when, in 1874, the North-West Mounted Police arrived on the Canadian prairies to maintain law and order and establish the institutions of Canadian civil government. In the years that followed, the disappearance of the buffalo herds and the influx of white settlers led to profound changes in the tribal life of the plains Indians. The Blood tribe, which was a part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, signed Treaty no.7 with representatives of the Canadian government [see Isapo-muxika; Alexander Morris] in 1877. By signing the treaty, the Indians agreed to give up their nomadic way of life and settle on reservations.

Starchild achieved prominence as a result of the murder of a NWMP constable in the Cypress Hills (Sask.). On 17 Nov. 1879 Marmaduke Graburn, a 19-year-old who had enlisted the preceding June, was shot and killed while riding out alone near Fort Walsh. No witnesses to the killing could be found, but from tracks discovered at the scene the police believed the murder had been committed by two Indians. Graburn was the first mounted policeman to be murdered since the arrival of the force in the west and the authorities were worried that unless his killers were quickly apprehended the NWMP would lose the respect of the Indians. All attempts to solve the crime came to nothing until the winter of 1880–81 when two Indians incarcerated at Fort Walsh informed the police that a Blood named Starchild had boasted of shooting Graburn. Starchild was believed to be in Montana and it was not until May 1881 that the NWMP learned he had returned to the Blood reservation near Fort Macleod (Alta). Shortly afterwards Starchild was arrested and charged with the murder of Graburn.

The trial took place at Fort Macleod on 18 Oct. 1881 and attracted a great deal of attention throughout the North-West Territories. The Indians saw it as a test of the impartiality of the white man’s laws. Many white settlers, on the other hand, assuming that Starchild was guilty, hoped for a verdict that would discourage any repetition of such acts. They believed that a verdict of not guilty would be interpreted by the Indians as a sign of weakness. The case was tried before Lieutenant-Colonel James Farquharson Macleod*, a magistrate and the commissioner of the NWMP, and Superintendent Lief Newry Fitzroy Crozier*, a justice of the peace. The jury of six white men, including former mounted policemen, deliberated for nearly 24 hours before returning a verdict of not guilty.

The decision of the jurors was felt by some to have been influenced by their fear of retaliation by the Indians. As one of the jurors pointed out later, however, the crown’s case rested entirely upon Starchild’s own boastful statement that he had killed Graburn. There was no corroborating evidence. Moreover it was not unusual for young Indians (Starchild was about 19 years old at the time of Graburn’s murder) to boast of deeds they had not actually committed in order to gain recognition. Most historians of the NWMP, however, have assumed that Starchild was the murderer. The truth of the matter will never be known.

In July 1883 Starchild was arrested for bringing stolen horses into Canada from the United States. Once again he appeared before Macleod. On this occasion he was convicted and given four years’ imprisonment with hard labour, a sentence which, by contemporary standards, was not unduly harsh. Starchild served his sentence at Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba. He was pardoned for good behaviour on 5 July 1886.

After his release from prison he returned to live on the Blood Indian reservation. Strangely enough, he was later employed by the NWMP as a scout. In 1888 two whisky traders were arrested as a result of his resourceful and determined action. “Out of several Indian scouts that I have tried none have proved to be worth their salt but Starchild,” wrote Richard Burton Deane*, the officer commanding the police post at Lethbridge (Alta). “He did some good work for us, and I do not expect to replace him.” Unfortunately, between April and December 1889 Starchild became involved in an affair with the Indian wife of a white man and the same officer had to discharge him.

Starchild believed that his life was protected by “strong medicine,” and that no harm could come to him as long as he did not take a woman. It was shortly after his romance with the white man’s wife that he died. His death, like those of so many of his fellow tribesmen, was caused by tuberculosis.

Glenbow-Alberta Institute, Elizabeth Bailey Price papers, 1922–36. Royal Canadian Mounted Police Arch. (Ottawa), Service file 335 (Marmaduke Graburn); R. N. Wilson papers. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1879, IX, no.52; 1880–81, III, no.3; 1883, X, no.23; 1889, XIII, no.17. S. B. Steele, Forty years in Canada: reminiscences of the great North-West . . . , ed. M. G. Niblett (Toronto, 1915; repr. 1972). J. P. Turner, The North-West Mounted Police, 1873–1893 . . . (2v., Ottawa, 1950). H. A. Dempsey, “Starchild,” Western Canada Police Rev. (Vancouver), 7 (1953); reprinted in 15 (1961): 6–16.

Cite This Article

S. W. Horrall, “KUKATOSI-POKA (Starchild, Kucka-toosinah),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kukatosi_poka_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kukatosi_poka_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | S. W. Horrall |

| Title of Article: | KUKATOSI-POKA (Starchild, Kucka-toosinah) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |