Source: Link

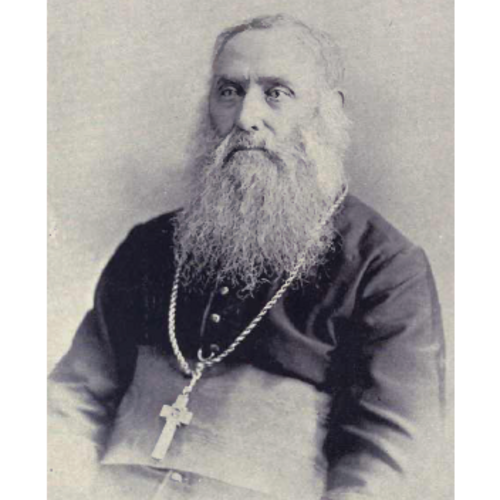

DURIEU, PAUL (baptized Pierre-Paul), Oblate of Mary Immaculate, Roman Catholic priest, missionary, and bishop; b. 4 Dec. 1830 in Saint-Pal-de-Mons, dept of Haute-Loire, France, second son of Blaise Durieux and Mariette Bayle; d. 1 June 1899 in New Westminster, B.C.

Paul Durieu’s family, landowning small farmers, sheltered priests during the reign of terror following the French revolution and later showed further devotion to the Roman Catholic Church by allowing Paul and his elder brother to attend the Petit Séminaire de Monistrol-sur-Loire. Influenced by boyhood dreams of foreign mission work, the reading of histories of North American missions, and a recruiting visit to the seminary by Father Jean-Claude-Léonard Baveux*, Paul entered the Oblate noviciate at Notre-Dame de l’Osier in October 1848. He made his profession on 1 Nov. 1849, and then undertook his scholasticate at Marseilles. He was ordained priest there on 11 March 1854 by Bishop Charles-Joseph-Eugène de Mazenod, founder of the Oblates.

Durieu had learned at Marseilles about the methods used by the Oblates in evangelizing the poor and re-establishing the church in Provence after the revolution. Members of the congregation toured the country holding sessions of instruction lasting from two to six weeks. During these “missions” they taught the elements of the Catholic faith in Provençal and emphasized music, penances, and grand penitential processions. Itinerant priests organized lay people to reinforce their teaching and carry on regular devotions in their absence.

As a seminarian, Durieu received no special training for his future work among the Indians of North America, but he did have the general instructions of Bishop Mazenod, who recommended using native languages, establishing mission schools, and avoiding direct involvement in the government of a tribe. Furthermore, when Durieu and Pierre Richard, both recently ordained, were delayed six months in their departure for the Oregon missions, the bishop sent them back to Notre-Dame de l’Osier to study English and review their theology. In the early 1840s the Oregon country had been served only by French Canadian secular priests [see Modeste Demers*] and by European Jesuits [see Pierre-Jean De Smet*]. The first Oblates had come in 1847 to assist the missionaries from Lower Canada, and in 1851 they set up the Oregon vicariate (which included the southern part of present-day British Columbia).

Almost immediately on his arrival in Olympia (Wash.) in December 1854, Durieu was sent by the local Oblate superior, Pascal Ricard, to assist Father Charles Pandosy in the Yakima valley. At the mission of St Joseph d’Ahtanum, Durieu learned about the Indians and their languages, and about the methods of evangelization used by the missionaries in the area. From their posts the Oblates went on tours of Indian camps by canoe and on horseback, sleeping under the stars and eating whatever was available. Like the Lower Canadian missionaries, they used the “Catholic ladder” of François-Norbert Blanchet, archbishop of Oregon [see Modeste Demers], and established temperance societies, stressed the use of music and of Indian languages, and encouraged native catechists and moral watchmen among each band of converts. The watchmen would inform the itinerant priests about transgressions, and together they presided over public confessions and decreed penances.

Durieu learned also of the difficulties faced by the Oblates in attempting to establish self-supporting farming missions among the tribes east of the Cascade Mountains. The Indians preferred to remain in separate groups, each roaming over a huge territory, rather than settle together at the mission. The English-speaking, mainly Protestant settlers and American government officials, hungry for Indian lands, mistrusted Catholic missionaries, especially the French-speaking Oblates. Durieu soon joined veteran Oblate missionaries in their enthusiasm for the Jesuits’ long-range plans for solving these problems. According to the Jesuits’ modified scheme, based on local experience and the model villages established by their order in 17th-century Paraguay, the mission post and chapel would serve as headquarters for colourful ceremonies adapted to native patterns, as well as for priests going out to visit various tribes. Agricultural villages would be a long-term goal. This gradual process would allow the settlements, or reductions, to be the focus of religion and examples for the future, but they would not be communal villages of several tribes.

The Yakima Indian war, which broke out in the winter of 1855–56, forced Pandosy and Durieu to flee their mission and take refuge at the Jesuit mission of St Paul’s, near Fort Colvile (near Colville, Wash.). The Oblates were impressed by the kindness of the Jesuits and by their modified reduction. In 1856 continuing warfare in the Yakima valley and disputes with the French Canadian bishops Augustin-Magloire Blanchet* of Nesqually and his brother François-Norbert caused Father Louis-Joseph d’Herbomez*, recently appointed visiteur extraordinaire of the Oblate missions in Oregon, to remove his men to coastal missions near Olympia. He assigned Durieu to assist Father Eugène-Casimir Chirouse the elder at Tulalip (Wash.) with the Snohomish, a Salish tribe. Durieu observed the success of Chirouse’s mission sessions, ceremonial gatherings, and attempts to establish a model village and school.

Meanwhile, poor relations with the church hierarchy and the American government led d’Herbomez to move all the Oblates except Chirouse north to British territory. Establishing his new headquarters at Esquimalt, he placed the congregation under the protection of Bishop Modeste Demers of Vancouver Island and officers of the Hudson’s Bay Company. In 1859 Durieu was assigned first to parish work with settlers in Esquimalt, and then to Kamloops in the interior of the recently created colony of British Columbia. There he took over from Father Pandosy as director of missions to the Interior Salish of the Thompson and Okanagan valleys. In this capacity he helped develop d’Herbomez’s plans for church-centred mission posts in each region, separated from the debaucheries of white settlements. From these posts, itinerant priests served native missions and temperance societies, and encouraged Catholic ceremonials in place of traditional ones. While on tour Durieu also vaccinated Indians against smallpox.

In 1864 d’Herbomez, now titular bishop of Miletopolis and vicar apostolic of British Columbia, called Durieu to his headquarters in New Westminster to assist in his work with the settlers and the Salish of the Fraser valley. The following year the bishop sent him to supervise St Michael’s mission to the Kwakiutls near Beaver Harbour, Vancouver Island, who had resisted earlier attempts to convert them.

Durieu was recalled to New Westminster in 1867 to serve as the bishop’s assistant and as director of St Mary’s mission in the lower Fraser valley. D’Herbomez counted on Durieu, with his experience at Tulalip, to develop the mission and its boarding-schools. The boys’ school had been founded by the Oblates in 1863 and the girls’ would be opened by the Sisters of St Anne [see Marie-Angèle Gauthier] in 1868. Durieu continued the practice of displaying the boys’ band on public holidays in New Westminster and used the band and the girls’ choir at grand Christian ceremonies (dubbed “potlatches” by the press) held before gatherings of Indians at St Mary’s mission. He toured native villages throughout the St Charles mission district (the Fraser valley and the coast), which included the Salish living on the Fraser River and the Strait of Georgia. The temperance society courts, presided over by the visiting priests, heard cases of drunkenness, gambling, and sexual immorality. In this early period these courts prevailed in the administration of civil law in the Indian villages of British Columbia. To help with the linguistic requirements of this work Durieu and his assistants began to publish religious literature such as the catechism, songs, prayers, and biblical history in native languages and in the Chinook trade jargon. His Chinook Bible would appear in 1892. It is not surprising that by the end of the 1860s the Indian chiefs of the lower Fraser were calling on them to draft petitions and letters of concern to the British Columbia colonial government regarding their lands. The government had denied the Indians treaties and guarantees for existing and future reserves.

Durieu rose quickly in the mission and church hierarchy. D’Herbomez left his vicariate in Durieu’s hands when he went to Europe in 1869 to attend the Vatican Council. The following year Durieu was appointed vicar general, and in 1873 he attended the Oblates’ general chapter in France. On 24 Oct. 1875 he was consecrated titular bishop of Marcopolis and became d’Herbomez’s coadjutor. As coadjutor bishop, he helped establish town parishes, schools, and hospitals, and he toured interior missions such as the old one at Stuart Lake in 1876, the new one at Kootenay (St Eugene) in 1877, and the Cariboo mission (St Joseph) in 1878. He requested federal assistance for Indian schools, the model agricultural reserve of Seabird Island, and Indian land claims. On trips to France and central Canada in 1873–74 and 1879 he helped recruit missionaries. He directed newly arrived missionaries such as Nicolas Coccola and Adrien-Gabriel Morice* and lay brother Patrick Collins, supervised the Oblates’ field-work, and cheered them at spiritual retreats. He encouraged francophones to study English and both francophones and anglophones to learn Indian languages. On the way back from his second journey to France he taught Father Jean-Marie Le Jeune the Chinook jargon, and he later encouraged him to publish the Kamloops Wawa, a newspaper containing articles on religious topics in Chinook, English, and French for distribution among the local Indians.

In particular Durieu became known for the retreats he arranged at mission centres, including St Mary’s, Squamish, Sechelt, and Kamloops. These gatherings, attended by up to 3,000 Indians from southwestern British Columbia, confirmed the faithful in their beliefs and helped spread new devotions and new lay associations such as the Honour Guard of the Sacred Heart. After the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, tourists and missionaries from the North-West Territories attended the June reunions for the feast of Corpus Christi. They saw crowds of devout Indians camped by band under the flags of the temperance societies, listening to sermons in native languages, singing in their own languages and in Latin, and attending dramatic processions. Visitors to the new city of Vancouver looked across Burrard Inlet to the Squamish mission and saw a local example of an Oblate model village in operation.

Privately bishops d’Herbomez and Durieu were concerned about problems behind the seemingly successful reunions and mission villages. In each of the Oblate mission districts numbers of natives persisted in their traditional religions. Many abused alcohol. Few became farmers, especially if seasonal wage labour or traditional economic supports were available. Residential schools at the missions failed to attract or keep masses of pupils. Disease reduced Indian populations. The economic booms of the late 19th century, creating occupational and recreational opportunities in construction camps and towns, assisted native opponents of missionary work. So did the continual shortage of Oblate priests and brothers. Moreover, Protestant settlers and government officials were often suspicious of Oblate work on Indian petitions and in schools. In the Fraser valley, Methodist schools and model villages competed with Oblate efforts, and Anglican bishop Acton Windeyer Sillitoe copied their “Christian potlatches.”

In 1888 Durieu was appointed vicar of missions (provincial) of the Oblates. After d’Herbomez’s death in 1890 he became bishop of the new diocese of New Westminster and vicar apostolic of British Columbia. His assistant was the young Bishop Augustin Dontenwill, born in Alsace but trained at the College of Ottawa, where he had taught languages. Durieu’s reports to the general chapters of 1893 and 1898 detail the scope of their charge. To serve the increasing immigrant population and more than 70 Indian village churches, they had two dozen priests, a dozen lay brothers, and four small groups of sisters. Durieu established a seminary in New Westminster and attempted to set up a noviciate for native sisters at Williams Lake in order to provide future staff. Meanwhile he continued the system of itinerant priests. The annual gatherings of Indians at central missions seemed to flourish, especially in places such as the devout village of Sechelt, where there was no resident priest until 1901. Durieu was also successful in promoting devotions to the Virgin and to the Blessed Sacrament. In 1894 he dedicated the grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes at St Mary’s mission in fulfilment of a vow made by his predecessor. At the same time a dream he had shared with d’Herbomez was realized when federal funds were obtained for boarding-schools there, at Kamloops, and at St Eugene in the Kootenays. Sisters of the Child Jesus were recruited to help staff the schools.

Bishop Durieu’s continued difficulties with native resistance, Protestant opposition, and the press of settlement on formerly isolated mission villages were highlighted by the Chirouse scandal of 1892. In the spring of that year Father Eugène-Casimir Chirouse the younger, nephew of Durieu’s mentor at the mission to the Snohomish, was charged in civil court for approving an excessive sentence of whipping handed down by a missionary court near Lillooet to a young girl charged with a sexual offence. Although Durieu succeeded in having Chirouse pardoned, he feared the disgrace of a missionary. It would, he claimed, “undo all the good accomplished for the Indians” by the Roman Catholic missionaries, and the Indians would be deprived of “their immemorial rights to regulate the private affairs of their people.”

After this incident Durieu sought legal status for the Indian Total Abstinence Society of British Columbia, and codified existing prohibitions in its rules. He had Father Chirouse organize, anonymously, ever grander mission reunions featuring dramatic tableaux of Christ’s Passion, which were soon applauded as native “Passion plays.” These efforts did help draw Indians away from traditional ceremonial dances, from the syncretic Indian Shaker Church at Puget Sound, Wash., and from the evil attractions of white towns. They also won the approval of the press in an anti-Catholic era and in a largely Protestant white community.

By 1897 Dontenwill had been made coadjutor to the ageing, ill Bishop Durieu and the following year he replaced him as vicar of missions. In 1898 Durieu made a final trip to France to attend the Oblates’ general chapter. The following January he went to the Squamish reserve to bless St Paul’s Indian boarding-school. On 1 June 1899 he died of stomach problems. Tributes at his funeral in St Peter’s Cathedral in New Westminster lauded his missionary and administrative work for the Roman Catholic Church and especially for the Indians. He was buried beside Bishop d’Herbomez at St Mary’s mission.

Historically Durieu has been most noted for the “Durieu system,” a strict Roman Catholic tribal theocracy he administered in southwestern British Columbia. Although it encouraged missionaries to use native languages, the system opposed Indian religious traditions. Historical accounts of its operation are found in the writings of two French Oblates trained by him, Morice and Émile-Marie Bunoz. An anthropological account was published in 1954 by the American anthropologist Edwin McCarthy Lemert.

Recent research on the Oblate missions in British Columbia has raised questions, however, about these earlier interpretations and their modern variants. It now appears that the Oblate mission system was not Durieu’s alone but was a composite with roots in the work of Jesuits in Quebec and Oregon and in Oblate experience in France and the Red River colony. Most of its elements were in place before Durieu arrived from France in 1854. Then, at a time when Catholic missionaries were faced with anti-Jesuit feeling and with Protestant competitors such as William Duncan*, Durieu allowed young Morice to write enthusiastic public relations pieces glorifying him personally. There are indeed hints in correspondence by fathers Pandosy, Richard, and Léon Fouquet that Durieu was considered by some to be egotistical for arrogating to himself the fame due to an entire group of pioneer Oblates. After Durieu’s death, Morice and Bunoz, involved in a struggle with Irish members of their order, continued heady praise of their early French superior. Unfortunately some modern scholars do not delve beyond these partisan accounts, which served as major sources for Lemert’s anthropological discussions of Durieu’s system. Nor do they consult a range of original mission and press reports on Oblate work and the persistence of native customs and religion. They ignore the fact that Durieu’s system allowed certain social and cultural practices to continue and that mission gatherings often included traditional feasting, horse-racing, and canoe-racing.

The Oblate approach did seem to work for a time in the late 19th century in relatively isolated missions like Sechelt and the Okanagan. It did not function well, however, in the increasingly urban Fraser valley. The system was not fully applied in the Cariboo mission until Father François-Marie Thomas arrived in 1897, and in New Caledonia (Our Lady of Good Hope mission) until Morice left in 1905. Two generations of 20th-century anthropologists have carved careers out of studying the survival of cultures that Durieu’s missionaries supposedly eradicated.

As more records become available on Durieu, and as bilingual scholars begin to exploit them, he will be seen more in the round, as an administrator, founder of missions, and aide to the Indians. The skill with which he managed available personnel while restricting internal quarrels will be recognized. His willingness to allow for native adaptations of Catholic practice, despite his devotion to his own beliefs, will be appreciated. The stern, clear directions he gave to missionaries in rough frontier situations, such as those contained in his letters to Father Jean-Marie LeJacq, will come to be seen in context and not as evidence of Jansenist or autocratic views. Further evidence on his personality will be found in his genial letters to his family in France and to young missionaries in the field, as well as in Squamish and Sechelt traditions about him.

Paul Durieu is the author of a Bible history that was transcribed into Chinook shorthand by Jean-Marie Le Jeune and published at Kamloops, B.C., in 1899 as Chinook Bible history. Le Jeune also compiled and transcribed Practical Chinook vocabulary, comprising all & the only usual words of that wonderful language . . . , issued in mimeograph form (Kamloops, 1886), and a second edition, Chinook vocabulary: Chinook-English . . . (mimeograph, Kamloops, 1892), which he attributes to Durieu’s research, although Pilling’s Chinookan bibliography (cited below) states that Durieu “modestly desclaimed authorship” of this work. Several unpublished religious works by Durieu are listed in “Catalogue des manuscrits en langues indiennes; conservés aux archives oblates, Ottawa,” Gaston Carrière, compil., Anthropologica (Ottawa), new ser., 12 (1970): 159–61.

A letter from Durieu to his parents, dated 1 July 1859, appears in the Annales de la Propagation de la Foi (Lyon, France), 32 (1860): 262–79.

AD, Haute-Loire (Le Puy), État civil, Saint-Pal-de-Mons, 4 déc. 1830. Arch. Deschâtelets, Oblats de Marie-Immaculée (Ottawa), ms Division K-75 (Indian Soc. of Total Abstinence, agreement of Sliammin mission, 4 Jan. 1904); Oregon, 1, b-xii, 4; c-vii, 2; c-xi-1 (Durieu corr). Arch. générales des oblats de Marie-Immaculée (Rome), Dossier Colombie-Britannique, acte de visite d’Aimé Martinet, Sainte-Marie, 18–25 sept. 1882; Dossier Paul Durieu; Dossier L.-J. d’Herbomez (copies at Arch. Deschâtelets). Arch. of the Diocese of Prince George, B.C., L.-J. d’Herbomez, circular, 7 Feb. 1888; letter to Durieu, 12 March 1882; Paul Durieu, acte de visite, Notre-Dame de Bonne Espérance, 28 sept. 1876; letters to Bunoz, 1892–95, esp. 22 April, 6 May, 1 Oct. 1892; letter to d’Herbomez, 14 March 1882; pastoral letter, 21 Nov. 1890 (photocopies at St Paul’s Province Arch., Oblates of Mary Immaculate, Vancouver). NA, RG 31, C1, 1881, North (New Westminster): 35. PABC, GR 1372, F 503, nos.1a, 2–2a, 4. B.C., Legislative Assembly, Sessional papers, 1876: 161–328. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1873–79 (annual reports of the Dept. of Indian Affairs). “The first bishop of New Westminster,” Missionary Record of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate (Dublin), 9 (1899): 377–78. Missions de la Congrégation des Missionnaires Oblats de Marie Immaculée (Marseilles; Paris), 1 (1862)–40 (1900). Petites Annales de la Congrégation des missionnaires oblats de Marie-Immaculée (Paris), 9 (1899): 280–84. British Columbian, 13 Feb. 1861–27 Feb. 1869, 7 Feb. 1885. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 23 Jan. 1873; 12 Aug., 28 Oct. 1875; 19 Jan., 8 Feb., 7 April, 23 Aug. 1877; 14 Oct. 1879; 22 Oct. 1880; 26 Oct. 1887; 31 Aug. 1888; 5 Dec. 1889; 1 Jan., 10 May 1891; 6, 10, 12, 31 May, 5, 12 July 1892; 2 June 1899. Daily Columbian, 8 Feb., 13 June 1887; 15 May, 23 June 1888; 31 Aug. 1889; 5, 7 June 1890; 10 May, 5 July 1892; 29 May, 1–2, 6 June 1899. Mainland Guardian (New Westminster, B.C.), 7–14 Aug., 16–30 Oct. 1875; 11–14, 23 Oct. 1879. Vancouver Daily Province, 1, 5 June 1899; 1, 4 June 1901. Vancouver Daily World, 4 June 1890; 1, 5–6 June 1899. Gaston Carrière, Dictionnaire biographique des oblats de Marie-Immaculée au Canada (3v., Ottawa, 1976–79). J. C. Pilling, Bibliography of the Chinookan languages (including Chinook jargon) (Washington, 1893); repr. as his Bibliographies of the languages of the North American Indians (9 parts in 3 vols., New.York, 1973), 3, pt.7 : 44–45. P. Besson, Les missionnaires d’autrefois; Monseigneur Paul Durieu, o.m.i. (Marseille, 1962). Kay Cronin, Cross in the wilderness (Vancouver, 1960). R. [A.] Fisher, Contact and conflict: Indian-European relations in British Columbia, 1774–1890 (Vancouver, 1977). R. A. Fowler, The New Caledonia mission: an historical sketch of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate in north central British Columbia (B.C. Heritage Trust, New Caledonia heritage research report, Burnaby, 1985). Donat Levasseur, Histoire des missionnaires oblats de Marie Immaculée: essai de synthèse (1v. paru, Montréal, 1983– ). A.-G. Morice, History of the Catholic Church in western Canada from Lake Superior to the Pacific (1859–1895) (2v., Toronto, 1910). David Mulhall, Will to power: the missionary career of Father Morice (Vancouver, 1986). Bernard de Vaulx, D’une mer à l’autre: les oblats de Marie-Immaculée au Canada (1841–1961) (Lyon, 1961). Margaret Whitehead, The Cariboo mission (Victoria, 1981). B.C. Catholic (Vancouver), 4 Oct. 1953; 16 Aug., 8 Nov. 1981; 13 June 1982; 25 Nov. 1984. É.-[M.] Bunoz, “Bishop Durieu’s system,” Études oblates (Ottawa), 1 (1942): 193–209. Fraser Valley Record (Mission, B.C.), 9 Dec. 1948, 20 July 1949, 25 Oct.–8 Nov. 1950, 13 Nov. 1957, 15 June 1983. E. McC. Lemert, “The life and death of an Indian state,” Human Organization (New York), 13 (1954–55), no.3: 23–27. R. M. Weaver, “The Jesuit reduction system concept: its implications for northwest archaeology,” Northwest Anthropological Research Notes (Moscow, Idaho), 11 (1977): 163–77.

Cite This Article

Jacqueline Gresko, “DURIEU, PAUL (baptized Pierre-Paul),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/durieu_paul_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/durieu_paul_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacqueline Gresko |

| Title of Article: | DURIEU, PAUL (baptized Pierre-Paul) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |