Source: Link

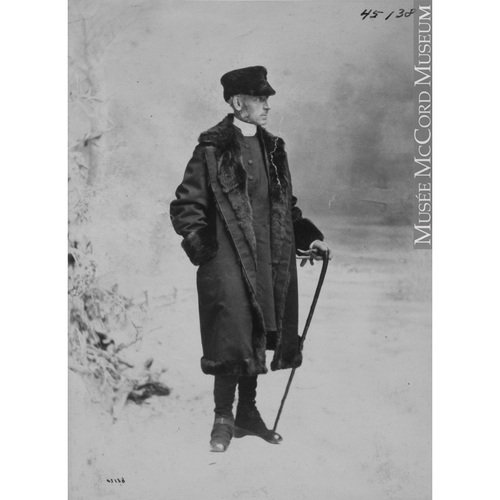

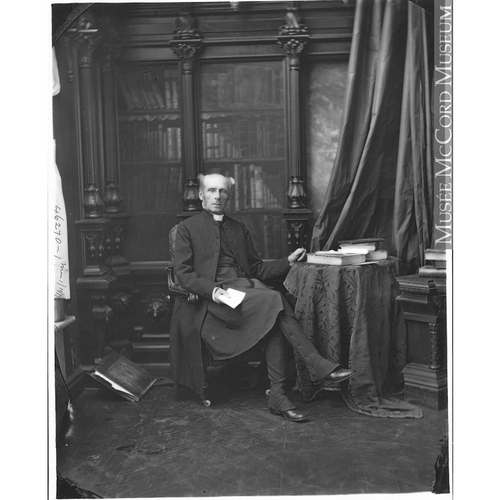

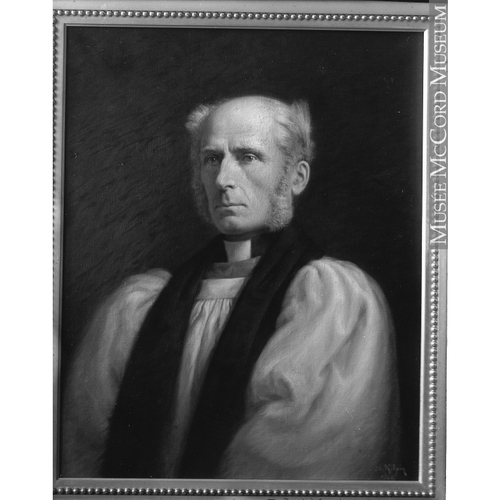

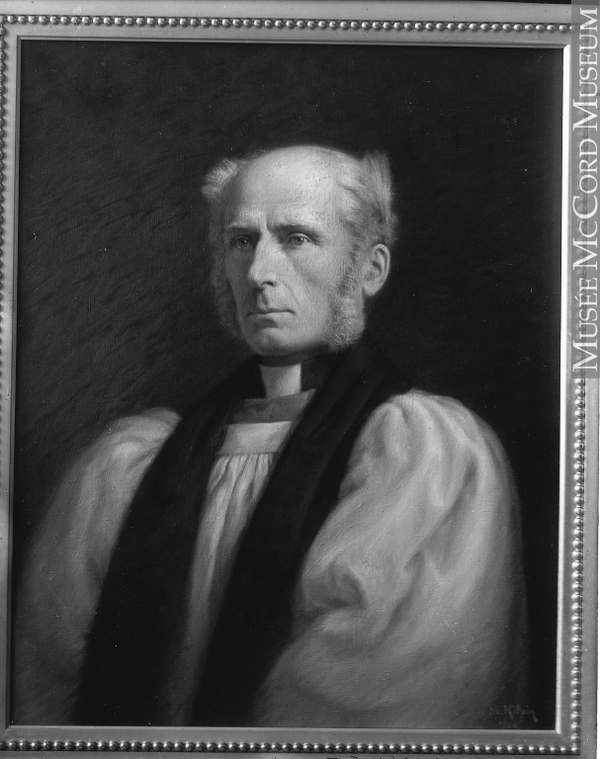

OXENDEN, ASHTON, Church of England clergyman, bishop, and author; b. 28 Sept. 1808 in the parish of Barham, Kent, England, son of Sir Henry Oxenden and Mary Graham; m. 14 June 1864 Sarah Bradshaw in Bournemouth, England, and they had one child; d. 22 Feb. 1892 in Biarritz, France.

The son of a country squire, Ashton Oxenden enjoyed a happy childhood on his father’s estate at Barham, Broome Park, despite the death of his mother when he was six years old. He played cricket with his six brothers (he also had five sisters), hunted, and was whisked over Barham Downs on the family “sailing machine,” a 35-foot, cutter-rigged, four-wheeled land boat invented by his father. He attended Harrow from 1824, suffering the “tyranny of the older boys” until he rose to the top of his class in the third and final year. “As Captain I was a kind of autocrat,” he later recalled. “I certainly have never been so great a man since or ruled my fellows with so undisputed a sway.” Among his classmates were Christopher Wordsworth, later bishop of Lincoln, and Henry Edward Manning, subsequently a cardinal, with whom he also attended the University of Oxford from 1827. At University College, Oxford, he did not do so well. He missed all but the compulsory lectures to play cricket or to hunt. At one stage he was admonished by the dean “to hunt less, and to read more.” Then for six months in 1829–30 he was companion to an ill sister in the south of France, where he “learnt a little French [and] . . . got rid of many . . . prejudices,” but also contracted a sickness that became the basis of future delicate health. Back at Oxford, he did not excel at the examinations but none the less obtained a ba in 1831.

At a time when the Church of England and religion generally “were in a deplorable state of inanition,” according to his own assessment, and when it was his father’s desire that he enter the legal or diplomatic profession, Oxenden nevertheless chose the ministry. He was made deacon in 1832 and ordained priest on 22 Dec. 1833 by the archbishop of Canterbury in Lambeth Palace Chapel, London. In 1832 he was appointed curate at Barham, of which he knew every nook and cranny from childhood. The parishioners were for the most part common agricultural labourers, and their “kind of feudal attachment” to their aloof young minister touched and transformed him, even though they did not shrink from saying what they thought; on the occasion of his first sermon, for example, a churchwarden remarked, “Let me give you my advice, and that is, to cut it short.” To enliven their religion he innovated in the services and renovated in the church. In outlying parts of the parish he gave “Cottage Lectures.” About all of these methods he admitted that “there was a little tinge of irregularity” in a period of stifling orthodoxy, and he did not always bother to inform the archbishop of his initiatives.

Oxenden’s strenuous efforts at Barham eventually ruined his health, however, and to restore it he was obliged to suspend clerical duties for nearly a decade. He spent winters in Italy, Madeira, and southern France; at other times of the year he travelled to Switzerland, Germany, and Spain. He kept abreast of the controversy between evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics that threatened to divide the Church of England, but he refused to join one party or the other. Nevertheless, to the stress on apostolic succession and the sacraments of the Anglo-Catholics he preferred the evangelicals’ emphasis on a simple faith in Christ and the divine inspiration of the Bible, although he reproached them for their disregard of “church system.”

In 1848, after having been curate of Silsoe for six months, Oxenden became rector of Pluckley, another agricultural parish. Again he sought “to vivify and readjust the Church Services, to create a more reverential tone among the worshippers, and to breathe into them a warmer and livelier spirit.” Over the next 21 years he succeeded. In addition, between 1852 and 1857 he published 49 of the “Cottage Lectures,” which became known as the “Barham Tracts.” Their popularity inspired him to write another 67 pamphlets, known as the “Pluckley Tracts,” as well as some 25 books, a number of which attained sales of several hundred thousand copies. About 1858 he was elected a diocesan proctor (or clerical representative to convocation), in the following year he obtained an ma from Oxford, and in 1864 he was made an honorary canon of Canterbury Cathedral. His growing reputation, particularly as a writer, reached Canada, and one morning in the spring of 1869 he was astonished to find on his breakfast table an urgent invitation from the bishop of Quebec, James William Williams, to accept, if elected, the joint posts of bishop of Montreal and metropolitan of the ecclesiastical province of Canada.

The first incumbent of these offices, Francis Fulford*, had died in 1868, and the synod of the diocese of Montreal, after two sessions and 14 ballots in 1868–69, had been unable to agree on a successor. The two posts had been amalgamated by royal patent in 1860 with the result that the election of a bishop was constrained by nominations for metropolitan received from the provincial house of bishops. The differences between evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics had prevented agreement until, on 14 May 1869, the bishops proposed Oxenden and synod elected him immediately. Sixty years old and in delicate health, he initially refused, but on the urging of Bishop Williams and the Montreal synod, and after seeking advice from the archbishop of Canterbury and close friends, he accepted. On 1 Aug. 1869 he was consecrated at Westminster Abbey. The same year he received an honorary dd from Oxford.

The new bishop arrived at Montreal in late summer 1869 bringing important assets. His deep spirituality, his familiarity with convocations of bishops and clergy, which had been revived in the province of Canterbury, his friendship with Christopher Wordsworth, who believed that the laity should have a role in church government, and the popularity of his devotional writings all gave him the strength, experience, and respect he needed to govern a somewhat divided church. As well, his wide travels, particularly in France, helped him to adapt to Montreal and to the province of Quebec. He found his diocese “pretty well organized,” though lacking a residence for the bishop. He had one designed by John James Browne and constructed next to Christ Church Cathedral in 1871–72.

The poor financial condition of the diocese, especially in respect to its mission churches (those that were not self-supporting), required Oxenden’s immediate attention. To cope with a decline in the diocese’s annual grant from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, he established a “sustentation fund” in 1871 and urged church members to give more liberally to the mission fund. However, in part because of a depression in North America beginning in the 1870s, contributions to the latter showed only a modest increase, and he was obliged to limit the number of mission stations and the already meagre stipends of their clergy, decisions he found distasteful. To inspire financial assistance in England he published My first year in Canada (London, 1871), an entertaining description of Montreal and of his diocese, which he had by then visited extensively. His set-back in the local financing of missions notwithstanding, Oxenden argued that “our Church in Canada, needy as she is, would have a larger blessing if she did more for our brethren in distant lands.”

Oxenden’s early pastoral visits, which had doubled as reconnaissance trips, had convinced him that his clergy, numbering about 70 on his arrival, were not numerous enough for the task. His book had sought to stimulate the immigration of English clergymen to Montreal, but he realized that the formation of a native clergy was essential. In December 1869 he had visited Bishop’s College, which was charged with training clergy for the dioceses of Quebec and Montreal, and found it in need of “revival.” According to Oxenden, apart from having “earned the character (somewhat unjustly perhaps) of nurturing extreme opinions in its students,” Bishop’s had the misfortune to be “a tedious railway journey of six hours” from Montreal. As well, he was ex officio vice-president of the college, and he found its meetings “anything but agreeable, as there existed a strong sympathy in favour of Quebec, and sometimes a direct antagonism to Montreal.” His relations with its Anglo-Catholic principal, Jasper Hume Nicolls*, were strained. Thus, hoping to gather his candidates for the ministry in Montreal, where he could better superintend them, Oxenden proposed the establishment of a theological college there. However, finding firm opposition from “a decided majority of the clergy, and many also of our laity,” he took no action until June 1873 when the increasingly critical shortage of clergy moved him to undertake establishment of the Montreal Diocesan Theological College. It opened in September under the principalship of the Reverend Joseph Albert Lobley*, a non-partisan Anglo-Catholic and graduate of the University of Cambridge. By 1877 Oxenden could report to synod that he had “enough men . . . to meet our immediate needs.”

Oxenden also hoped, no doubt, that the college would enable him to obtain quietly a greater uniformity of ritual in the diocese. He wanted, for example, to introduce a common hymn book. Early in his episcopate he had come into conflict publicly with the Reverend Edmund Wood*, who had built up a church in a poor district of Montreal using Anglo-Catholic ritualistic practices that scandalized evangelicals. Relations between the two men remained tense throughout Oxenden’s term at Montreal.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the recurring conflicts between evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics, Oxenden found Montreal Anglicans “decided . . . , perhaps even more so than in England.” With Protestant denominations they had “a friendly rivalry,” he discovered, and their relations with the Roman Catholics were “kindly,” “each pursuing their own course without molesting the other.” All his life, however, Oxenden remained profoundly distrustful of Roman Catholicism, and he considered the “decided ascendancy” of the Catholics “one great drawback” to the success of his work. Despite his visits to France, he did not speak French fluently, and he seems to have used it only to address the francophone Anglican Abenakis of Saint-François-de-Sales (Odanak). He no doubt stimulated zeal in the women of his diocese, who, in 1873, formed the Ladies’ Association, in aid of Church Missions, to palliate his most urgent problem. Women had been forming associations in the parishes since the 1840s but this was their first diocesan organization. It also assisted Anglican students at the McGill Normal School, who were mainly female.

Like most bishops, Oxenden conducted his pastoral visits in the summer and fall, and his description of them makes it clear that he presided over a still largely pioneer diocese. “Sometimes I preached in loghouses, sometimes in school-rooms, sometimes in the most rustic churches,” he was to write in 1891. “Sometimes I passed over half-charred tracts, sometimes over roads which jolted one almost into a jelly. . . . From these official journeys I usually returned to Montreal or Lachine, pretty well knocked up.” In winter he expedited the accumulated diocesan business, entertained at Bishopscourt (sometimes 300 to 400 guests at a time), and participated in the gay social life of the city. But if he appreciated the snow-muffled quiet of Montreal winters, he fled the jarring noise and stifling heat of its summers, taking refuge in a riverside cottage at Lachine.

As metropolitan, Oxenden presided over five sessions of the synod of the ecclesiastical province of Canada. It was determined to avoid the problems of 1868–69 by removing the proviso that the metropolitan had to be the bishop of Montreal. The Montreal synod, over which Oxenden also presided, strongly opposed such a change. Relations between the two bodies became strained, and the question would not be settled finally until the early 1880s, although the house of bishops elected John Medley, bishop of Fredericton, as metropolitan in 1879. This tension no doubt added to the pressures that, meanwhile, had steadily eroded Oxenden’s health.

By 1878, in his 70th year, Oxenden found that he could no longer meet the demands of his position. In the spring he announced his intention to resign effective immediately after the Lambeth conference in London that summer. He left Montreal on 10 May 1878, spoke twice at the conference, and moved to southern France shortly after its close. He was succeeded in Montreal by the Reverend William Bennett Bond*. After acting as chaplain at Cannes in the winter of 1878–79, he was named rector of St Stephen’s Church, near Canterbury. Ill health again forced him to resign in 1885. The previous year he had spent seven or eight months in Biarritz, and he continued this practice, preaching or taking services in the English church there. In 1891 he wrote The history of my life; by that time he had authored some 32 books, one of which had sold more than 700,000 copies. Some of his devotional works had been translated into the Takudh and Cree languages of North America. He died, at age 83, in February 1892.

From necessity Oxenden had spent much of his life outside England, and, although to the end he loved England most, his travels had enabled him to adapt well to the peculiar social circumstances of the diocese of Montreal. At the same time, in a period of theological division he had sought always to bring peace and harmony to the church, a task often difficult to achieve in Montreal. His heart was with the evangelical view that a simple faith in Christ and an acceptance of the Scriptures were the real paths to salvation. His life and writings reflected that conviction.

Ashton Oxenden is the author of My first year in Canada (London, 1871) and The history of my life: an autobiography (London, 1891), as well as of many of the religious pamphlets listed at the back of the latter.

A portrait of Oxenden appears in O. R. Rowley et al., The Anglican episcopate of Canada and Newfoundland (2v., Milwaukee, Wis., and Toronto, 1928–61), 1: 50; F. D. Adams, A history of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal (Montreal, 1941), reproduces an oil painting held at the ACC, Diocese of Montreal Arch.

Arch. municipales, Biarritz, France, Service des arch. municipales, concession de terrain dans le cimetière de Biarritz, 22 févr. 1892. Dorset Register Office (Bournemouth, Eng.), Holdenhurst, reg. of marriages, 14 June 1864. Lambeth Palace Library (London), Lambeth Conference papers, 1878, LC 7; LC 8. Church of England, Diocese of Montreal, Journal of the synod (Montreal), 1868–81; Ecclesiastical Prov. of Canada, Journal of the proc. of the provincial synod (Quebec and Montreal), 1871, 1873–74, 1877, 1880, 1883. Edmund Wood, The catholic and tolerant character of the Church of England . . . (Montreal, 1871). DNB. J. I. Cooper, The blessed communion; the origins and history of the Diocese of Montreal, 1760–1960 ([Montreal], 1960). Oswald Howard, The Montreal Diocesan Theological College: a history from 1873 to 1963 (Montreal, 1963).

Cite This Article

Jack P. Francis, “OXENDEN, ASHTON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/oxenden_ashton_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/oxenden_ashton_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jack P. Francis |

| Title of Article: | OXENDEN, ASHTON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |