ANCIENT, WILLIAM JOHNSON, Church of England clergyman; b. 25 Feb. 1836 in Croft, Lincolnshire, England, son of William Ancient; m. 3 Feb. 1864 Emma Ann Mullett in London, England, and they had at least two sons and five daughters; d. 20 July 1908 in Halifax.

William Johnson Ancient entered the Royal Navy in 1854 as an ordinary seaman. He served initially in the Baltic during the Crimean War. Promoted leading seaman, he was subsequently in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean squadrons. Ancient left active service in 1863 and, following the required period of study, was appointed a scripture reader in 1864 by the Royal Naval Scripture Readers Society, which provided laymen to minister among the personnel of naval dockyards.

His initial posting was to Halifax. His abilities soon came to the attention of the local branch of the Colonial and Continental Church Society, a Church of England organization dedicated to planting and supporting teachers, catechists, and missionaries in communities incapable of sustaining independent church establishments. On 12 May 1867 Ancient was ordained a deacon for the mission of Terence Bay, a “destitute and desolate” fishing community some 15 miles southwest of Halifax. Within eight months he had revitalized the mission, closing in a church structure raised in 1853 and reporting in January 1868 that a new schoolhouse would be ready by the spring.

The diocese of Nova Scotia decided in 1871 to admit “well trained Scripture Readers” to the priesthood on certain conditions, and Ancient was ordained on 16 June 1872. He immediately left for England, in part to “seek improved health for his wife who had suffered much from the loneliness and privations of her situation.” Ancient was active during his time abroad in deputation work for the Colonial and Continental Church Society, preaching and recruiting potential missionaries for Nova Scotia.

Returning to Terence Bay, he found that matters had become “a little disordered . . . especially in connection with Rum.” By early 1873 he reported that he had to some extent succeeded in putting a stop to the problem. He also noted that his parishioners “think it hard that they cannot drink, fiddle and dance and yet be considered good church members.” For the most part, however, he accepted the rough ways of his flock, understanding that their lives were shaped by isolation and the sea.

In the spring of 1873 Ancient attracted worldwide attention for his involvement in one of the most spectacular North Atlantic marine disasters of the late 19th century. In the early hours of 1 April the Atlantic, a luxury liner of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company (commonly known as the White Star Line), ran onto Meagher’s (Mosher) Island, a mile from Terence Bay. The vessel, carrying 976 passengers on a regular run from Liverpool, England, to New York, had encountered heavy weather and was attempting to put into Halifax for coaling. Faulty navigation led it onto the rocks instead.

Within ten minutes the Atlantic broke up and began to sink. A line was secured to a nearby rock and from thence to the island, and in the darkness some 250 passengers were brought ashore. Rockets attracted the attention of fishermen from Lower Prospect, half a mile away, who arrived at dawn with three small boats. These boats saved upwards of 150 people by plucking them from the rock, eight to twelve at a time. Meanwhile, word of the tragedy had been relayed to Terence Bay, and a rescue party which included Ancient immediately set out.

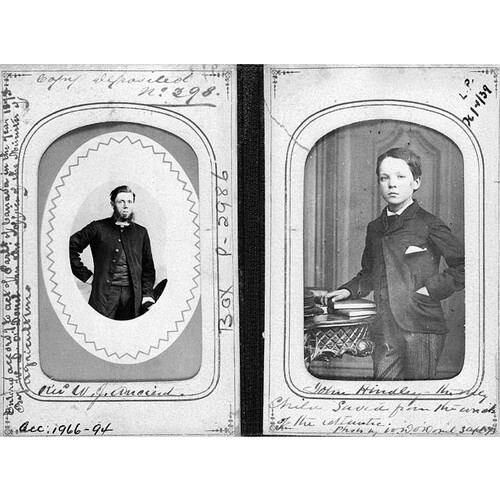

When the party arrived more than 400 survivors were huddled on the shore; well over 500 passengers had perished, including some 30 who had been clinging to the mizzen-mast rigging but had lost their grip. Three individuals remained in the rigging: the first officer, John W. Firth, a woman passenger whom he had tied to the rigging but who subsequently died from exposure, and a boy named John Hindley. The seas were so rough that none of the rescue boats dared approach the wreck, which was listing at a 50-degree angle.

At 2:00 p.m. Ancient asked some fishermen to row him to the wreck. They demurred, fearing his certain death, but he replied, “If I am doomed I won’t hold you responsible. Put me on board.” As they approached, Hindley fell from the rigging and was plucked from the roaring waters. Commanding all his expertise as a seaman, Ancient managed to scramble aboard and pass a line to Firth, who had been in the rigging for some ten hours. Ancient instructed the officer to “put your confidence in me and the Lord and move when I tell you.” As they struggled towards the boat, a huge sea swept Firth overboard, and in horror he cried out, “O Lord I have broken my shins. I have broken my shins,” to which Ancient roared, “Never mind your shins, man! It is your life we are after.” Buoyed by Ancient’s determination and resourcefulness, Firth was brought ashore. Every woman on board the great vessel had died, and Hindley was the lone child saved.

The international press seized upon the story of the Atlantic with a zeal surpassed only by that displayed when the Titanic sank nearly 40 years later. The local inhabitants were lauded, but Ancient was lionized for his achievement (which, although spectacular, had been merely the climax of a splendidly courageous effort by a community of seafarers). The press created a stalwart Victorian hero, “six feet in height and strongly built [with] a genial face, a bright eye, a clear head and a warm heart.” One burst of hyperbole described Ancient as a “man in a thousand . . . buried among his parishioners, 3,000 miles from home,” who toiled “day and night, educating the people, Christianizing, civilizing, and ruling them by love.” Apparently the heathen did not all reside in darkest Africa.

Official tributes followed quickly upon the press accolades. Ancient was honoured by the government of Canada, the Humane Society of Massachusetts, and the Citizens’ Relief Committee of Chicago. He accepted the awards graciously, but emphasized that his fellow rescuers had shown bravery, endurance, and humanity and that their failure to save Firth stemmed only from their lack of “knowledge of practical navigation in large vessels,” an expertise he had gained during naval service.

In many respects, the Atlantic affair was the signal event of Ancient’s life. The public attention it generated brought him to the notice of church officials, and he was offered an assistant curacy in St Paul’s parish in Halifax. He was to serve under the elderly James Cuppaidge Cochran* at Trinity Church, where “it was thought his zeal and ardent desire for the salvation of souls” would influence “the poor and seafaring men” who attended. Ancient was inducted on 29 June 1874.

In 1879 a parishioner left Trinity, complaining of Ancient’s “High Churchism.” Ancient refuted the charge in his only known published work, a series of dignified Lenten sermons delivered that year and published as The cross. In 1880 he was appointed rector of Rawdon, a rural parish. Although the transfer may have been deemed expedient, any damage caused by the incident at Trinity was transitory, since in 1890 Ancient was awarded an honorary ma by King’s College. The same year he was named rector of Londonderry, where he served the rough-and-tumble mining and industrial community at Acadia Mines.

Ancient’s high standing with church authorities was confirmed in 1895, when he was appointed clerical secretary-treasurer of the diocese of Nova Scotia, a position arguably second to that of the bishop. His final years were thus spent in administration, but the shift did not signal any diminution of his enthusiasm or energy; at his death it was remarked that “the various diocesan funds [were] now in so satisfactory a state” because of his care. In his memorial notice Bishop Clarendon Lamb Worrell* paid tribute to Ancient’s “sturdy type of character” and added that “on shipboard, in parish life and in the Synod office his sense of duty was plainly marked and whatever he did was done to the best of his ability and in singleness of purpose.”

William J. Ancient’s volume of sermons was published as The cross: being a course of sermons preached in Holy Trinity Church, Halifax, on the Sunday evenings in Lent, 1879 (Halifax, 1879).

ACC, Diocese of Nova Scotia Arch. (Halifax), Book of registry, vol.A. PANS, RG 40, 28, file 6. PRO, ADM 38/2666, 38/8517; ADM 139/102. Acadian Recorder, 3–4, 23, 28 April, 15 July, 8 Oct. 1873. Canadian Illustrated News (Montreal), 12 April 1873. Church Work (North Sydney, N.S.; Halifax), 15 May 1906, 13 Aug. 1908. Halifax Herald, 21 July 1908. Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 21 July 1908. Weekly Citizen (Halifax), 5 April 1873. P. R. Blakeley, “W. J. Ancient – hero of shipwreck Atlantic,” N.S. Hist. Quarterly, 3 (1973): 215–24. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Church of England in Canada, Diocese of Nova Scotia, Yearbook (Halifax), 1908–9. Colonial and Continental Church Soc., Halifax branch, Report (Halifax), 1862, 1866–67, 1872–74, 1891. Crockford’s clerical directory . . . (London), 1896. W. E. L. Smith, The navy chaplain and his parish (Ottawa, 1967).

Cite This Article

Lois K. Yorke, “ANCIENT, WILLIAM JOHNSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ancient_william_johnson_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ancient_william_johnson_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lois K. Yorke |

| Title of Article: | ANCIENT, WILLIAM JOHNSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |