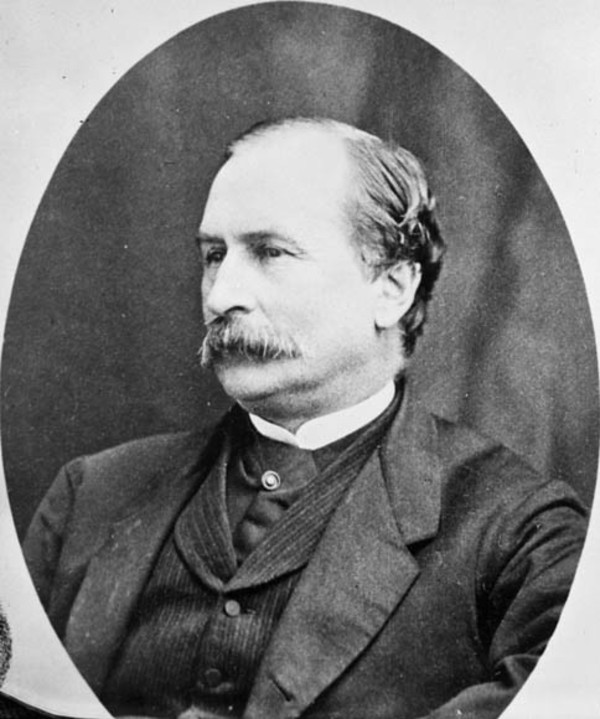

JONES, ALFRED GILPIN, businessman, politician, and office holder; b. 24 Sept. 1824 in Weymouth, N.S., son of second cousins Guy Carleton Jones and Frances Jones; m. first 17 July 1850, in Halifax, Margaret Wiseman Stairs, aunt of John Fitzwilliam Stairs, and they had seven children; m. secondly 5 April 1877, also in Halifax, Emma Albro; they had no children; d. there 15 March 1906.

Alfred Gilpin Jones’s loyalist grandfather Stephen Jones came from Massachusetts to Weymouth, then called Sissiboo, where he and his son Guy Carleton served in turn as registrar of deeds for many years. Educated in Weymouth and at Yarmouth Academy, Alfred Jones moved at age 18 to Halifax. There he became a bookkeeper and later a confidential clerk with Thomas Clifford Kinnear, West India merchant and shipowner. Made a partner as early as 1850, he established the firm of A. G. Jones and Company in the same line of business on Kinnear’s retirement in 1872. Relations between the two men remained cordial, and Jones was the chief executor of Kinnear’s will.

Jones quickly made his company a flourishing concern and built up a personal fortune. An agency for the Dominion Life Assurance Company helped A. G. Jones and Company expand rapidly, but the biggest boost to the firm occurred in 1899 when it became agent in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland for several large British steamship lines. Jones’s family continued the company after his death.

Although Jones was a Conservative and an admirer of his party’s nominal leader, James William Johnston*, and its de facto leader, Charles Tupper*, he was not active in politics until 1863. When the Liberals under William Young* had taken office following the disputed election of 1859, Tupper had set up the Constitutional League to raise constitutional arguments against them. In the election of 1863 Jones generally directed the league’s activities and received considerable credit for the Conservatives’ overwhelming victory.

The next year Jones’s political stance changed markedly. Against confederation almost from the start – he agreed with most of his fellow Halifax merchants that it would be ruinous to their interests – he came out openly on 23 Dec. 1864 at the first major anti-confederation meeting in Halifax. Asked to refute Liberal leader Adams George Archibald*’s favourable analysis of the financial provisions proposed for Nova Scotia, he contended that in order to maintain existing services the provincial government would have to “go to direct taxation on their own people in order to make up the deficiency.” Later he gave financial and moral support to the Anti-Confederation League (sometimes called the League of the Maritime Provinces), especially to its sending of Joseph Howe*, William Annand*, and others to London to oppose – unsuccessfully, as it turned out – the British North America Act. After suggesting that others were better equipped by public life and training, he reluctantly became a candidate for Halifax in the federal election of September 1867. Nova Scotians, he argued, were being told that they were “too ignorant and degraded to pass an opinion on a measure which is to affect them and their children forever.” One of 18 anti-confederates elected in Nova Scotia, Jones took the position that since he and his fellows had chosen to run under the imperial act of 1867 they would damage their case by not going to Ottawa. In his maiden speech in parliament he promised to “support good measures and oppose bad, without regard to either party.” His strongest attacks were on the new general tariff which, to him, imposed burdens on the eastern provinces in order to meet the needs of Quebec and Ontario.

Having failed to persuade the British government to repeal the BNA Act in 1868, the anti-confederates brooded over what to do next. In the autumn Howe on his own initiative entered into a correspondence with Sir John A. Macdonald*, and Jones was one of those to whom he turned for advice in framing his response to Macdonald’s overtures. Alarmed that Howe might be giving away his entire case, they got him to change the wording. Jones worried that Howe, used to dealing with the great questions of politics, did not fully grasp the details of the province’s financial arguments against confederation. Although he warned Howe not to show signs of weakness “until the people themselves see . . . the utter hopelessness of getting Repeal,” Howe entered the federal cabinet late in January 1869.

With Jones as a driving force the anti-confederates immediately formed the Repeal League, determined to end confederation by “all or any means consistent with the principles of Christianity.” As one of its vice-presidents, he used every weapon conceivable to try to defeat Howe in the by-election in Hants County made necessary by his entry into the cabinet, a contest Jones described as perhaps “the most important . . . that has ever taken place in British America.” To him votes for Howe were “votes for Canadian rule for ever.” Not only did he get Halifax merchants to provide campaign funds in abundance, but he and other anti-confederates contended with Howe in meetings at almost every hamlet in Hants. Using to the full the astounding memory and mastery of detail he applied to mercantile pursuits, he reviewed every step of Howe’s conversion to confederation as no one else did. How could Howe and one or two others have “the overweening vanity to take upon themselves the settlement of a question in which such large interests and so much feeling were involved?” Seemingly his treatment of his opponent grew harsher day by day. Howe lamented that, while he was lying at Nine Mile River in a state of collapse, Jones stood over him for more than an hour “declaiming, without having the common decency to enquire if I was ill.” Despite Jones’s efforts, Howe was victorious.

Jones never forgave the confederates for the means they had used to bring Nova Scotia into the union. He was, however, becoming sympathetic towards the federal Liberals. As early as the 1868–69 session of parliament, Jones established an alliance with Alexander Mackenzie*, both in person and through correspondence, and the tie would be a lasting one. Though Mackenzie supported confederation, he had not taken part in the tactics of effecting it; moreover, he and Jones held similar views on tariffs, government expenditures, and political corruption. In 1869 and 1870 Mackenzie expressed disappointment that Jones, who did not attend the sessions those years, was not present to act as Howe’s “chief opponent in your Province” and to “consolidate” the vote of the Nova Scotian mps. Although it is generally accepted that the Ontario Grits dominated the federal Liberals during the 1860s and 1870s, Mackenzie’s letters to Jones evince considerable solicitude towards Nova Scotians. Thus the Liberal attack of 1870 on the method of granting “better terms” to Nova Scotia was made, as Mackenzie explained to Jones, “in such a way as not to . . . hurt the sensibilities” of the province.

Jones strongly supported the Liberals in person in 1871. On the occasion of the first no-confidence motion of the session he was one of only two Nova Scotian mps to condemn the Macdonald government for its excessive expenditures, and he later opposed its plan to admit British Columbia into the union on the grounds that building a railway to the Pacific would result in “liabilities too great for [Canada] to bear.” The next year he severely criticized the Treaty of Washington for allowing Americans to fish in Canadian waters, calling Canadian control of them “the only [lever] we ever had to secure a fair measure of reciprocal trade between the two countries.” In the election campaign of 1872, again a reluctant candidate, Jones assailed the government’s treatment of Nova Scotia and defended his making common cause with the Liberals of Ontario and Quebec. The views of men like Mackenzie, Edward Blake*, Luther Hamilton Holton*, and Antoine-Aimé Dorion*, he said, were more in accord with his own and the interests of Nova Scotia than those of the governing party. He even justified their voting against better terms for the province, agreeing with them that any change in the “solemn compact” of union should be made, not by an ordinary act of parliament, but by constitutional means.

To Mackenzie’s “surprise and grief,” Jones lost narrowly. Over the next year the Liberal leader kept him informed of the movement of most Nova Scotian mps to become full-fledged Liberals as Macdonald’s government disintegrated because of the Pacific Scandal. Mackenzie would have liked to make Jones one of his two Nova Scotian cabinet ministers when the Liberals came to power in November 1873, but Jones was not in parliament and would not have accepted office in any case. The prime minister therefore let the Nova Scotian mps make the choice. Unfortunately for him, they picked Thomas Coffin*, a mediocrity, and William Ross, a hopeless misfit. After complaining to Jones of the incompetence of Ross, “a gobemouche,” Mackenzie was able to replace him as minister of militia and defence with William Berrian Vail in September 1874.

Pressed by his friends, Jones ran as a Liberal in the Pacific Scandal election of 1874, probably the strangest contest in the history of the Halifax constituency. Facing certain defeat, leading Conservatives did not nominate candidates of their own but allegedly entered into a conspiracy with working man’s candidate Donald Robb to oppose the Liberals. Jones and his running mate, Patrick Power*, were easy victors. A staunch defender of the government, Jones praised it in 1877 for administering the country “wisely, carefully, prudently and economically.” A year earlier he had strongly supported its repudiation of higher tariffs and, in effect, of Tupper’s views of a national policy. Montreal, Toronto, and Hamilton might disagree, but “there are more constituencies . . . which have larger interests involved than theirs, great as they are.” Mindful of the health of the party, in 1875 Jones sought with other prominent Liberals to effect a full reconciliation between Mackenzie and Blake, but they had indifferent success.

Always of independent mind, however, Jones occasionally vented his displeasure on actions of the government. In 1875 he voted against the bill to set up the Supreme and Exchequer courts – to him it was an expenditure of $100,000 for “something that the country did not need” – but justified his stance as opposition to a measure originally initiated by the Conservatives. The previous year his requests for patronage appointments in the railways had thoroughly perturbed the prime minister, who was adamant that the offices not be filled on political grounds alone, but attested at the same time that his “only object [was] to administer affairs to suit you and our friends.”

Late in 1877 Jones and Vail resigned when it became clear that they would be unseated because of a strict interpretation of the Independence of Parliament Act. The Halifax Citizen, in which they had small holdings, had received government printing contracts, but neither man was personally at fault since neither had been aware of the contracts. By-elections were held less than two weeks apart in January 1878. The Digby by-election came first, and after Vail lost there Jones was sworn in as his successor as minister of militia and defence. This act permitted the government to treat Jones’s victory in Halifax as a ministerial election, a proceeding denounced by the Conservatives as sharp practice.

Not inexperienced in military matters, Jones had been lieutenant-colonel of the Halifax Volunteer Battalion before organizing the 1st Halifax Volunteer Artillery Brigade in 1864. Refusing appointment under the federal Militia Act, he became a private in the unit which he had commanded. In his ten-month stint as minister no circumstances arose which tested him severely. Nevertheless, one observer wrote that he exhibited an acute grasp of departmental details and “a great capacity for a prompt, business-like discharge of public business.” During this short period, however, Jones faced a charge of disloyalty, the result of remarks he had allegedly made on the occasion of Governor General Sir John Young*’s first visit to Nova Scotia in 1869. The accusation had been made before, and the instigator on both occasions was Tupper. Jones was strongly defended by Mackenzie, and nothing came of the incident.

When the Conservatives campaigned on the National Policy in the fall 1878 election, Jones called it a “tortuous and hypocritical” platform. Was not the United States, a long-time practitioner of protection, suffering as much from the economic depression as Canada? How could protection provide relief from the only competition which affected Nova Scotia manufacturers, that of Ontario and Quebec? The arguments were unavailing; the Liberal government lost, as did Jones in Halifax. In 1882 he ran again and took special aim at the National Policy and Tupper. “When a man is very ill, he is ready to listen to any one who offers relief, although the proferer may be a quack.” With zest he pointed out the failure to make Halifax the winter port for shipping grain or to bring the railway repair shops back from Moncton, N.B. It was not enough, although he came within 65 votes of winning.

In the federal election of 1887 Jones found himself caught up in the campaign to repeal the BNA Act. The previous year William Stevens Fielding*’s Liberals had swept the province on the question. A year later Nova Scotia’s Liberal candidates ranged from ardent repealers such as John Lovitt to stout non-repealers such as Vail. By now Jones was unsympathetic to repeal, but he did not repudiate it because it was the policy of the provincial government. Instead he argued that the Liberals could get reciprocity and access to natural customers. At the same time he condemned Conservative corruption. To him, comparing Macdonald to Blake and Mackenzie was like comparing Benedict Arnold* to George Washington or Judas Iscariot to the apostle Paul. As for Tupper, he was another Lord Castlereagh; just as Castlereagh had bartered away Ireland’s liberties, so Tupper had Nova Scotia’s. Although repeal and Jones’s running mate were beaten, he himself headed the poll in Halifax. An active parliamentarian over the next four years, he as usual emphasized financial and tariff matters: in 1887 he condemned extravagant undertakings “which the condition of the country does not warrant”; in 1888 he ridiculed as a “complete absurdity” the attempt in Tupper’s budget to forecast what interest rates would be in ten or fifteen years; and in 1890 he protested a specific increase in tariffs because they imposed a heavy burden “upon a class of people who are the least able to bear these taxes.”

The 1891 election saw Jones going all out for unrestricted reciprocity. Scorning cries of loyalty from his opponents, he suggested that Tory loyalty was “stirred to its very depths when . . . they can have the old flag – ‘and an appropriation.’” When Jones lost badly, the Halifax Morning Chronicle attributed his defeat to “unparalleled . . . open, barefaced bribery.” He expressed disappointment that voters could “prove so blind to their own interests” but consoled himself that in his case, unlike the Tories’, “no man can point the finger to any relative of mine [ever] drawing a cent of public money.” The Halifax Conservatives having been unseated after legal challenges, Jones contested a by-election in early 1892 in which the chief Conservative campaigner was Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*. Probably no one ever sought to show more often that Thompson’s statements were “utterly at variance with truth.” Although bluntly suggesting that someone “compelled to make such sacrifices” as giving up one’s business and home comforts in the public interest should get vigorous support, he lost again, but cut the Conservative majority by more than half.

By 1894 Jones realized that his active campaigning was over. Age had taken its toll and he refused a federal nomination in 1896. When the Liberals won and Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier* chose Fielding as his minister of finance, it must have caused severe wrenching to Jones. After he had been Nova Scotia’s chief federal Liberal for three decades with indifferent success, someone else had assumed the role easily and quickly with the party in power. Perhaps it was with a touch of jealousy that he chided Laurier for regarding Fielding as “a little Tin God on Wheels.” But he too had his rewards: appointment in 1896 as one of Canada’s representatives on the Imperial Pacific Cable Committee and, on 26 July 1900, as lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia. He held the latter office until his death. As lieutenant governor, he was not called upon to deal with any important constitutional issue. According to the Morning Chronicle, Government House was free from “idle pretentiousness [and] vulgar display” and “characterized by a democratic simplicity [that] catered to no class or caste.”

Jones’s community activities included service on the boards of Dalhousie University and the Halifax Protestant Orphans’ Home. In businesses other than his own he was president of the Nova Scotia Marine Insurance Company and a director of the Acadia Fire Insurance Company. As a West India merchant he was in close touch with the commercial pulse of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and even Canada. His major speeches – perhaps two hours in length – were often replete with mercantile and financial details, factually unchallengeable, and delivered with an absence of rhetoric and bombast. By his supporters he was considered a “powerful, persuasive and eloquent speaker . . . listened to with rapt attention.” But to other voters he may have appeared ponderous and too fond of detail; certainly he seemed to lack a sense of humour and anything resembling a light touch. These deficiencies may have hurt him in his political battles, particularly those with Tupper.

Between 1867 and 1891 Jones won only four of nine elections. In the same period Nova Scotia’s federal Liberals had genuine success only in 1867 and 1874, whereas the provincial Liberals lost but once, in 1878. Since confederation had tended to make Nova Scotia a Liberal province, what is the principal reason for the relatively poor showing of Jones and the federal party? It may have resulted in part from the fact that the Conservatives were given the chance to label them little Canadians. Among the federal Liberals there was a paucity of new and positive thinking, and Jones’s role was almost exclusively that of a critic. A foe of extravagance, he tended to regard large public undertakings such as the Pacific railway to be beyond the capacity of the country to sustain. The free trader par excellence, he scornfully dismissed the prospects for development allegedly inherent in the National Policy. Furthermore, although Jones was adept at defending his own conduct and in exposing the delinquencies of his opponents – with the result that the Conservatives seldom ventured personal attacks on him – he never really mastered the art of politics as Tupper did. He would likely have replied that others had employed tactics to which he would never resort.

[Material concerning Alfred Gilpin Jones’s family and career is found in CPG, 1905; in Biographical review . . . of leading citizens of the province of Nova Scotia, ed. Harry Piers (Boston, 1900), 15–17; and, to a lesser extent, in the Stayner collection at PANS, MG 1, 1649. An account by Jones of Halifax life from 1842 to 1864 appears in “Reminiscences,” six articles in the Halifax Morning Chronicle, 2–18 Jan. 1892. The obituary articles and editorials of 15–16 March 1906 in the Morning Chronicle, Halifax Herald, and Acadian Recorder provide useful information and comment on Jones, as does “An occasional’s tribute” in the Acadian Recorder of 19 March 1906. Secondary sources touching on his political career include my Joseph Howe (2v., Kingston, Ont., and Montreal, 1982–83), 2, and my Politics of N.S.

Many letters from Alexander Mackenzie to Jones are reproduced in “Letters of Hon. Alexander Mackenzie to Hon. A. G. Jones, 1869–85,” PANS, Board of Trustees, Report (Halifax), 1952, app.B. Some of these letters are placed in context in Dale C. Thomson’s study Alexander Mackenzie, Clear Grit (Toronto, 1960).

The most significant item in the small collection of Jones papers at PANS, MG 1, 523, is his letter-book while minister of militia and defence. The remaining contents, several folders of miscellaneous public and private documents in a somewhat disorganized state, are of minimal value. Other relevant materials at PANS include the Joseph Howe letters in MG 1, 475–76 (typescript); a collection of newspaper clippings relating to Jones’s activities in provincial and federal elections, MG 1, 1308; and documents referring to the disloyalty charges of 1878, MG 100, 170, nos.14, 16; and 183, no.6.

For Jones’s speeches on the hustings (most of them lengthy), I relied primarily on the Morning Chronicle; the Halifax Citizen was also consulted for the period up to 1877. The House of Commons Debates for 1867–72, 1874–78, and 1887–90 record his speeches and were extensively used, as were the House of Commons Journals for 1871. Editorial comment in the Halifax British Colonist, the Morning Chronicle, and the Morning Herald (later the Halifax Herald) was examined where appropriate. j.m.b.]

Cite This Article

J. Murray Beck, “JONES, ALFRED GILPIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jones_alfred_gilpin_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jones_alfred_gilpin_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. Murray Beck |

| Title of Article: | JONES, ALFRED GILPIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |