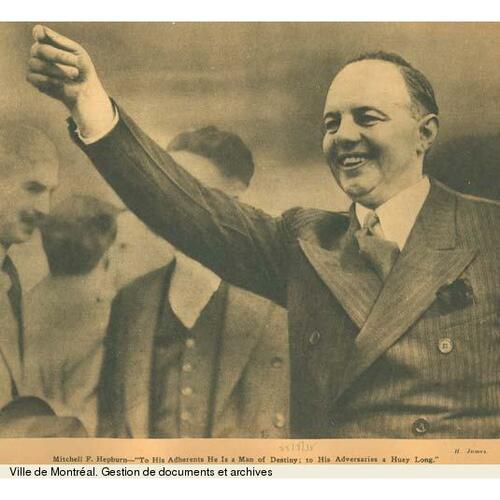

![Description English: Mitch Hepburn Source: Archives of Ontario Date: [Between 1934 and 1942] Creator: Photographer unknown. Date 2006-11-08 (original upload date) Source Originally from en.wikipedia; description page is/was here. Author Original uploader was YUL89YYZ at en.wikipedia Permission (Reusing this file) PD-CANADA.

This image is available from the Archives of Ontario This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information. English | Français | Македонски | +/−

Original title: Description English: Mitch Hepburn Source: Archives of Ontario Date: [Between 1934 and 1942] Creator: Photographer unknown. Date 2006-11-08 (original upload date) Source Originally from en.wikipedia; description page is/was here. Author Original uploader was YUL89YYZ at en.wikipedia Permission (Reusing this file) PD-CANADA.

This image is available from the Archives of Ontario This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information. English | Français | Македонски | +/−](/bioimages/w600.2594.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HEPBURN, MITCHELL FREDERICK, bank clerk, farmer, and politician; b. 12 Aug. 1896 in Yarmouth Township, Ont., son of William Frederick Hepburn and Margaret Jane Fulton; m. 11 Sept. 1918 Eva Maxine Burton in St Thomas, Ont., and they had two children, one of whom was stillborn and the other died in infancy; they later adopted a son and two daughters; d. 5 Jan. 1953 in Yarmouth Township.

Mitchell Hepburn’s paternal grandfather and namesake, “Old Mitch,” had emigrated with his family from Scotland to Elgin County, Upper Canada, in 1843 as a lad of nine. By 1900 he was among the most prosperous farmers in the area, working more than 600 acres while holding mortgages on several neighbouring properties. He and his wife, Elizabeth (Eliza) Johnson, had four children, but none lived past childhood. They informally adopted a son born out of wedlock to one of their servants and named him William Frederick. Convivial and energetic, Will followed his adoptive father into the Liberal Party and was twice nominated as a federal candidate for Elgin East. The second time, in 1906, he withdrew before the election amidst charges of sexual indiscretion. Will moved west, first to St Paul, Minn., where he was joined by his wife, Maggie, and their two children, Irene (born in 1895) and “Young Mitch” (born a year later), and then to Winnipeg. Homesick and disheartened by her husband’s financial struggles, Maggie returned with the children to Ontario in 1910.

Mitch attended school in the St Thomas area. Although an exceptional student in history at the local high school, he distinguished himself most notably by getting suspended for allegedly dislodging the bowler hat of a visiting dignitary, Adam Beck*, chairman of the province’s Hydro-Electric Power Commission, with a well-aimed apple. Rather than apologize for something he claimed he had not done, Mitch quit school at the age of 16 and got a job at the local Merchants’ Bank of Canada; he moved to the Canadian Bank of Commerce a few weeks later. When his mother went back to Winnipeg in 1913 in a short-lived attempt at reconciliation with her husband, Mitch was transferred to the bank’s branch in that city. After the outbreak of World War I, the young man, already a volunteer in the 34th (Fort Garry) Horse, sought to enlist, but he was slightly under the minimum age and his parents refused their consent. Four years later, shortly after he was ordered to report for duty, he transferred to the Royal Air Force and was sent to Deseronto, Ont., for training. Injuries in an automobile accident that summer, which would be followed by influenza in the fall, kept him from active service but did not prevent him from marrying his sweetheart, Eva Maxine Burton, in September. “Old Mitch” gave him 200 acres to launch his career, and he would acquire more acreage after his grandfather’s death in 1922. By the mid 1920s Hepburn was a prosperous and progressive farmer, ready to follow his father into politics.

In the 1919 provincial election, Hepburn had cast his ballot for the fledgling United Farmers of Ontario, which formed a government under Ernest Charles Drury*. For several years he served as secretary of the UFO’s local riding association. But after the party’s decisive defeat in 1923 at the hands of George Howard Ferguson*’s Conservatives, Hepburn moved back to the party of his father and grandfather. During the 1925 federal contest, he stumped the Elgin West riding for the Liberal candidate. His fiery oratory and youthful enthusiasm prompted the Grits to offer him the Liberal nomination there a year later. Though his mother sought to dissuade him, he finally accepted on 12 August, his 30th birthday.

When an election was called for 14 September, after the defeat of the short-lived government of Arthur Meighen, Hepburn, with barely four weeks to campaign in a traditionally Tory riding, had his work cut out. He ran as an independent Liberal, the better to appeal to former UFO supporters and Tory-leaning railway workers in St Thomas. Campaigning on a pledge to lower tariffs and freight rates, he benefited from the 1924 Liberal budget, which had reduced taxes, thus diminishing the cost of an automobile, which was becoming a popular acquisition. His boundless energy, spontaneous wit, and rhetorical eloquence scored well against the incumbent, Hugh Cummings McKillop, a low-profile Tory backbencher. When the votes were counted, Hepburn had reduced the usual Conservative margin in the urban polls while reaping strong majorities in the rural townships. From a deficit for the Liberal candidate of nearly 2,000 votes in 1925, he emerged the winner by 178 votes a year later. In a night of upsets across the country, it was one of the most unexpected results.

Over the next four years, the brash young Hepburn evolved from a restless maverick backbencher to a rising star in the government ranks. Initially, he chafed at the restrictions placed upon rookie mps, even threatening to cross the floor and sit with the Progressives. After a chat with Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King*, however, Hepburn began to carve out a more constructive role. By 1928 he was one of the designated Liberal speakers during the budget debate, and two years later he was asked to rebut the Conservative veteran Henry Herbert Stevens* on tariff policy. Meanwhile, on the hustings he had used his platform skills to advantage in a key by-election in Huron North in 1927 and out-duelled Tory backbencher Eccles James Gott at a well-attended public debate in St Thomas. Still, he only reluctantly supported a Liberal bill to crack down on liquor smuggling into the United States. Though Hepburn was rumoured to savour life in the fast lane, his disinclination was actually rooted in the knowledge that the measure was deeply unpopular in his home region.

By 1930, when the next federal election was called, he had developed a reputation as a diligent constituency representative, solid committee member, and energetic spokesman for Ontario farmers. His public clash with James J. Morrison* of the UFO, whose views on group-based government he found repugnant, cemented his image as the progressive voice of pro-Liberal agriculturalists. Moreover, his denunciation in 1928 of a private bill to recapitalize the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, which he charged with blatant “stock-watering” that would adversely affect policy holders, had solidified his populist appeal to the average Ontarian. Though the Conservative machine of Premier Ferguson targeted his riding for special attention in the federal campaign, Hepburn easily won re-election, despite a national swing towards Richard Bedford Bennett*’s Tories as the Great Depression tightened its grip.

Although he was fully engaged in his own riding, he had found time to speak elsewhere in Ontario for fellow Grits. In the special autumn session of parliament that followed the election, he no longer languished on the back benches. King seemed dispirited and passive, but the “boy from Yarmouth,” as he was dubbed by political journalists of the day, carried the fight aggressively against the Conservative government. When a provincial by-election was called in Waterloo South in October, Hepburn was happy to help in what turned out to be an unexpected Liberal victory. By this time, powerful figures in the provincial wing of the Ontario Liberal Association were beginning to take notice. At a meeting of the Toronto Men’s Liberal Club that month, Hepburn produced a barn burner of a speech. The premier, he declared, was one of only two absolute monarchs in the world, the other being the king of Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Few others in politics could spark such a roar of approval from a simple comparison of Howard Ferguson and Emperor Haile Selassie.

Out of office since 1905 and still reeling from the worst election defeat in their history in 1929, provincial Liberals were looking for a charismatic figure to bring them back to power. Perhaps now was the time to reach beyond the tiny caucus at Queen’s Park. Certainly, William Edmund Newton Sinclair*, who had served as acting leader since 1923, was well past his prime. Indelibly linked in the public perception to the Prohibitionist wing of a faction-ridden party, he offered only principled ineffectiveness, and a movement developed to draft the rising star from Elgin West into the provincial leadership. From behind the scenes, King tried to head it off: he feared the unpredictability of his high-spirited and irreverent junior colleague and also the probable loss of the young mp’s seat to the Tories in any subsequent by-election. Hepburn remained coy, choosing to spend an extended Florida vacation with his wife and his mother – an astute symbolic gesture for someone widely reputed to be a drinker and a womanizer. In his absence the drive to co-opt him continued to gain momentum. At the convention in Toronto, which opened on 16 Dec. 1930, one nominee after another dropped out, including Sinclair. In the end, Hepburn prevailed over Elmore Philpott*, an assistant editor with the pro-Liberal Toronto Globe, by a wide margin. At the age of 34, he became the youngest person ever to lead the Ontario Liberals.

For the next three years Hepburn criss-crossed the province, seeking to breathe life back into the party organization. Though he retained his federal seat, he devoted most of his time to provincial affairs. His goal was to unite all farmers and workers who opposed the Conservative government of the new premier, George Stewart Henry, behind himself and the Liberal Party. Harry Corwin Nixon*, the leader of the rurally based Progressives, was an old friend from Hepburn’s days in the UFO and equally in favour of a coordinated effort. Appealing to urban workers was more problematic, especially after the formation of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation in 1932–33. In an attempt to attract the support of labour, Hepburn sharpened the tone of his rhetoric. “I swing well to the left,” he claimed during a by-election in York West in 1932, “where even some Liberals will not follow me.” When the Henry government sent troops into Stratford a year later to break a strike in the furniture factories, Hepburn spoke up for the workers.

The three defining issues of the day for the province were hydroelectricity contracts with private suppliers, the sale of beer and wine, and increased tax support for Roman Catholic schools. In each case, Hepburn sought to keep his party united, while pressing the attack on Premier Henry. Increasingly, he came into conflict with Sinclair, his own house leader, who did not hide his antipathy towards the new chief. Nevertheless, a series of by-elections in which the Liberals either triumphed or significantly reduced Tory majorities revealed an unmistakable trend. Hepburn’s own health remained delicate. (He had had a kidney removed in June 1931.) Bursts of strenuous activity were interspersed with lengthy periods of rest, either on the farm or in Florida. Invariably, after the requisite time out, he would sweep back onto the political stage, as bold and colourful as ever. It was a pattern that his own federal leader, King, could neither understand nor condone.

Though Hepburn confessed privately to one correspondent that his political career was “one hell of a rotten game, and many times I have wished that I had never started in it,” he did not convey this impression in public. Henry challenged him to secure a seat in the provincial legislature, offering an acclamation, but Hepburn refused to take the bait. Yet behind the scenes he acted to have Sinclair replaced as house leader by the party whip, George Alexander McQuibban, on the eve of the 1934 session. In March the Conservative government introduced amendments to the Liquor Control Act designed to ease restrictions on the sale of beer and wine by the glass while, at the same time, driving a wedge between the “wets” and the “dries” in the Liberal caucus. Hepburn and his followers responded by issuing a public statement that “the position of the Opposition … is that Prohibition is not and should not be made a political partisan issue.” Though six Liberals, including McQuibban, broke ranks to vote against the proposed legislation on second reading, Hepburn assured voters that, if elected, a Liberal government would adopt the Tory bill. With the temperance issue temporarily out of the way, he resumed his overall strategy to keep the Tories on the defensive. In achieving this goal, the Liberals benefited from their increasingly close cooperation with Harry Nixon’s Progressives. When the legislature was dissolved in mid May and an election was called for 19 June, Hepburn resigned his federal seat to run provincially in Elgin. The Liberals were, for the first time in a generation, fully competitive with their Conservative adversaries. The campaign would prove decisive.

The 1934 Ontario election was an old-fashioned mud-slinging contest. Henry chose to stand on his record, hopeful that the reviving economy, his government’s recovery measures, and the vaunted Tory party machine would determine the outcome. For good measure, he slammed his opponent as a dangerous radical whose swing to the left would prove disastrous for the province. Hepburn replied in kind. The campaign was not a week old before he had unleashed pointed charges against the Conservatives concerning an elaborate “toll-gate” scheme, by which they had allegedly profited from the granting of licences to sell products to the province’s Liquor Control Board. From one end of Ontario to the other, he accused the Tories not just of corruption but, worse, of running a bloated, inefficient administration. In a typical platform promise, the opposition leader pledged to line up the government limousines at Queen’s Park and auction them off to the highest bidder. The Conservative-leaning Toronto Evening Telegram published a private letter circulated by the Catholic Taxpayers’ Association of Ontario, which was pressing both parties about funding for separate schools. The letter urged Catholics to vote against the government, and so the Tories accused the Liberals of a back-room deal. Hepburn stoutly denied any inappropriate promises and in turn sarcastically reminded voters of how “Honest George” Henry had somehow forgotten that he owned $25,000 in bonds issued by a company his government had bailed out of financial difficulty. Significantly, the Liberal organization was as well funded and effective as its Tory adversary. Hepburn’s patient wooing of Progressive and Labour supporters over the previous four years vastly reduced the number of three-cornered fights in which the anti-government vote was split. When the votes were counted on 19 June, the outcome was a Liberal landslide. The combined Liberal, Progressive, and UFO forces had won 70 seats in a legislature of 90. Just over 50 per cent of voters had chosen Grit candidates or their allies. At 37, Mitch Hepburn was about to become the youngest premier in Ontario history.

After a few days for celebration and recuperation, he moved to put his stamp on provincial affairs. He and his cabinet, reduced to ten members as an economic measure, were sworn in on 10 July. His Progressive ally Harry Nixon, who became provincial secretary and registrar, would prove a solid second-in-command. Other prominent appointments included Toronto barrister Arthur Wentworth Roebuck* as attorney general and minister of labour and David Arnold Croll*, a former mayor of Windsor and the first Jewish cabinet member in Ontario’s history, to head public welfare and a new department responsible for municipal affairs. Hepburn intended to run a tight ship and would serve as his own provincial treasurer. One of the cabinet’s first decisions was the proclamation of the beer and wine measure introduced by Henry’s government. The ministers’ main focus during their first six months in office was to eliminate wasteful expenditures. Starting with themselves, they reduced their own salaries by $2,000, a cut of 20 per cent. Eighty-seven government-owned automobiles were auctioned off at the University of Toronto’s Varsity Stadium. Numerous high-profile Conservative appointees, including members of the Hydro-Electric Power Commission and George Alexander Drew*, chairman of the Ontario Securities Commission, were summarily fired. Ontario House in London, England, was closed. Game-wardens, bee-keeping inspectors, and driving examiners were among the minor officials whose positions were eliminated. In all, Hepburn claimed that these economic measures would save a million dollars, and more were promised. Several inquiries were established to investigate alleged Conservative misdeeds in office. Hepburn still found time to attend a dominion–provincial conference in Ottawa in July and to participate vigorously in five federal by-elections held in Ontario in September, four of which resulted in Liberal victories. The frenetic pace was taxing his personal health, however, and late in the year he took two holidays, one with some of his cronies in the Caribbean and the other with his wife, Eva, in Florida.

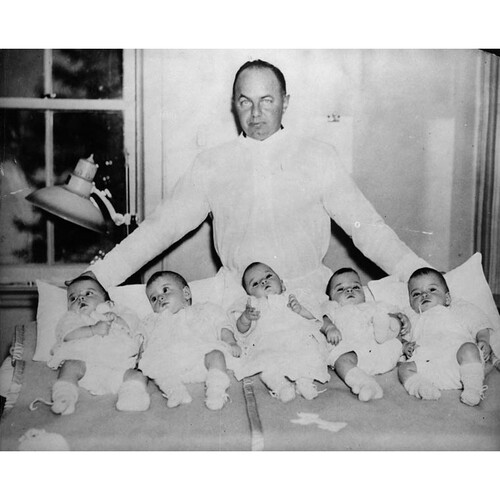

Tanned and fit, Hepburn returned to Ontario for the opening of his first legislative session in February 1935. As a symbolic gesture in the midst of the Great Depression, he and his cabinet declined to attend the lieutenant governor’s traditional state dinner on the eve of the session, and it was cancelled, but he donned the requisite formal attire for the reading of the throne speech. The new premier quickly moved to assert his dominance in the legislature, brooking no dissent from caucus members and occasionally utilizing his party majority to overturn rulings of the speaker. On 2 April he brought down his first budget, aided immeasurably by a dedicated civil servant, Chester Samuel Walters, who served as controller of finance in the Department of the Provincial Treasurer. Through the paring of expenditures and increases to gasoline and estate taxes, Hepburn was able to halve the deficit inherited from the Henry administration. The most controversial measure of the session was Roebuck’s Bill 89, the Hydro-Electric Power Commission Act, 1935, designed to repudiate hydroelectricity contracts signed by the Conservative government with four Quebec companies. Passage of this legislation against determined Tory opposition required a 26-hour, non-stop debate. Other noteworthy achievements included a bill to make the Dionne quintuplets (Yvonne, Annette, Cécile, Émilie, and Marie), who had been born near Callander in May 1934, wards of the provincial government; the Industrial Standards Act, which brought in minimum wages and created voluntary codes to guide labour relations; a new welfare policy that established provincewide standards for eligibility and capped contributions from Queen’s Park to municipalities; and the conversion of maturing provincial bonds to lower-interest securities. Through it all the premier continued to burn his candle at both ends, partying late into the night at his suite in the King Edward Hotel, despite suffering periodic bouts of high blood pressure, insomnia, heart palpitations, and bronchitis. Meanwhile, anonymous threats to his family, which now included an adopted son, led the provincial police to establish protective surveillance around his farm.

Nevertheless, when the federal election campaign began in the summer of 1935, Hepburn stumped the country energetically in support of the Liberal cause. For six weeks he travelled from coast to coast, logging over 10,000 miles and delivering upwards of 65 speeches. He encouraged his cabinet colleagues and the provincial party organization to “go the limit” in ensuring the success of Liberal candidates. When the votes were counted, King’s Ontario caucus had mushroomed from only 22 seats in 1930 to 56 five years later, and the Liberals had been returned to power with a large majority. It was thus a bitter pill for Hepburn to swallow when his request that an ally, Arthur Graeme Slaght*, be included in the new federal cabinet was ignored. Though King had welcomed Hepburn’s help in getting re-elected, he was suspicious of the premier’s motives and leery of his control over the Liberal party machine in Ontario. The developing animosity between the two Grit chieftains soon became apparent at the dominion–provincial conference held in Ottawa in early December. The federal and Ontario delegations clashed over a number of issues: the advisability of debt conversion to lower interest rates, federal assistance for welfare expenditures, and the taxing of mining profits and succession duties. Hepburn’s harried state of mind may be gleaned from a statement he had issued to the press in early November, indicating his intention to retire after the next legislative session. “My two enemies, fatigue and worry, pursue me relentlessly on this job,” he explained. Another lengthy Florida vacation seemed to ease the tensions, for nothing more was heard about retirement upon his return to Canada in late January.

The Liberal leader was pleased with his March budget, which forecast a modest surplus for the upcoming fiscal year, largely as a result of the vigilant enforcement of succession duties and a new tax on those with incomes over $1,000, a comparatively large sum at the time. But it was the separate-school funding issue that dominated provincial politics in 1936. The British North America Act of 1867, which had guaranteed the right of Catholic schools in Ontario to tax support, had not anticipated the age of large business corporations devoid of religious affiliation. Consequently, the public-school system received the lion’s share of municipal taxes, only partially offset by provincial grants. Catholic ratepayers, believing Hepburn’s Liberals would be more apt than Henry’s Conservatives had been to redress the imbalance, had swung to him in 1934. Two years later the premier undertook to justify their support with legislation that would establish a division of municipal corporate taxes more in line with the religious composition of the province. The bill, introduced in the legislature in early April, was controversial from the start, prompting a filibuster from the Tories. In the face of bitter opposition from large segments of the Protestant majority, Hepburn appealed to Ontarians’ sense of justice. After a week of impassioned speech making in the legislature, the premier whipped his caucus into line to pass the bill in a vote held at 5:00 a.m. on 9 April. Later in the year the issue would dominate a by-election in Hastings East, which drew in heavyweights from both parties. Even Hepburn’s personal popularity could not tip the balance in the predominantly Protestant riding, however, and the Conservatives held it with an increased majority. The premier faced another disappointment in November, when the Hydro-Electric Power Commission Act nullifying contracts with four Quebec companies was declared ultra vires in the courts. And his feud with Ottawa continued, exacerbated by unilateral federal cuts to welfare assistance. At the end of 1936 a frustrated Hepburn informed Norman Platt Lambert*, King’s chief party organizer, of his intention to “keep our organization separate and apart from yours.”

The new year did not begin well. The premier’s health took a turn for the worse, necessitating another southern holiday. The cabinet was divided and the caucus restive when Mitch returned in February to take charge again. He was able to bring in a balanced budget in March that included some modest tax cuts, increased subsidies to municipalities for township roads, and began to pay down the provincial debt. After assuming control of the hydroelectricity negotiations, Hepburn reached a settlement with the Ottawa Valley Power Company that lowered the cost per kilowatt from the original deal. His government also made the great white trillium (trillium grandiflorum) Ontario’s floral emblem. After several months of religious controversy and growing evidence of the administrative complexity created by the separate-school funding legislation, Hepburn unexpectedly led his party to support a Conservative motion to repeal the act. Catholic supporters were disappointed, but they appreciated that, in a province with a Protestant majority, he had done all he could. In a move that some attributed to his friendship with mine owners based in Toronto’s financial district, the Hepburn government announced a one-dollar-per-ton subsidy for iron ore extracted in the province, ostensibly to promote economic recovery.

In a similar vein, the premier sounded a warning against the new American-based Committee for Industrial Organization and its radical methods. He was convinced that the CIO would bring ruin to the Ontario economy if it was allowed to organize the province’s mines, mills, and factories. Following a bloody attack on strikers in a Sarnia foundry, Hepburn declared that he would not tolerate sit-down strikes in Ontario. This pronouncement seemed to contrast with his views before he came to power, when he had denounced the Henry government for calling in troops to end the Stratford strike of 1933 and proclaimed that his sympathies lay “not with the manufacturers” but with the workers.

He chose to make his stand at Oshawa, where 4,000 auto workers were engaged in contract negotiations with General Motors of Canada. With a recovering economy driving the market for new automobiles, management was prepared to accommodate union demands regarding wages, seniority, and working conditions, but the sticking point was recognition of the union itself. The Oshawa workers had formed a local of the United Automobile Workers of America, a key affiliate of the CIO. Hepburn encouraged the company to stand its ground, and a walkout followed on 8 April. Anticipating violence, he requested an emergency deployment of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, but when the King government hesitated to double the initial contingent, the premier ordered the Ontario Provincial Police to recruit several hundred special constables, quickly dubbed “Hepburn’s Hussars” or, sometimes, “Sons of Mitches.” There was no violence, but each time a settlement seemed close, it broke down over Hepburn’s insistence that there must be no involvement of American union organizers. The premier’s hard line divided his cabinet, and he asked for the resignations of the attorney general, Arthur Roebuck, and the labour minister, David Croll, who were not in agreement with his actions. The latter famously replied: “My place is marching with the workers rather than riding with General Motors.” After two weeks Hepburn was finally able to announce a settlement, which the workers ratified the next day. While the premier was convinced that he had held the line against the CIO, the union organizers also claimed victory.

During the Oshawa strike, Hepburn gave vent to what many considered his true motivation concerning the extension of the CIO, with its radical methods and Communist sympathizers, into the province. On 18 April he publicly warned the organization’s leaders that they would “never get their greedy paws on the mines of Northern Ontario” as long as he was premier. Encouraged by his Bay Street crony, financier Clement George McCullagh, now proprietor of the Toronto Globe and Mail, Hepburn went so far as to contact the new leader of the Conservatives, William Earl Rowe*, with a secret offer of a coalition government. Completely taken aback, the Tory chieftain consulted colleagues in Ontario and Ottawa and then declined. When rumours of the unprecedented initiative surfaced in the Toronto Daily Star, both leaders denied them. Hepburn’s reason for proposing an alliance, when he already dominated the provincial scene, remains a mystery, but it is perhaps best explained by his ardent desire for a united front against the CIO combined with a growing resolve to oust King as prime minister. The example of a strong non-partisan administration in Ontario, he seems to have hoped, might hasten the departure of his federal nemesis.

Though the scheme collapsed, Hepburn emerged unscathed, still riding high on the momentum generated by his public confrontation with the CIO. Although only three years into his mandate, the premier called a snap election for 6 October and launched an energetic campaign. He still claimed to be the champion of the “little man,” defending Ontario from scheming Communists, greedy power barons, and narrow-minded Tories. Ever the populist on the hustings, the Liberal leader evoked his rural roots, declaring, “I have faith in the intelligence of people.” Rowe criticized the government for repudiating contracts, exacerbating religious divisions, and violating workers’ rights, but with little success. It was another sweep for Hepburn’s party; the Liberals marginally increased their share of the popular vote and lost only a couple of seats. Mitch was at the peak of his political career.

The first order of business was to reconstruct the cabinet. In addition to filling vacancies, Hepburn added four ministers. The most prominent new member was the attorney general, Gordon Daniel Conant, whose victory in his Oshawa-centred riding seemed an endorsement of the government position in the recent strike. The reliable Harry Nixon continued as the leader’s right-hand man, ready to step in as acting premier during Hepburn’s frequent southern holidays. Barely had the new ministers been sworn in when the premier became embroiled in another dispute with King. The issue was the naming of a new lieutenant governor and the fate of Chorley Park, the official residence of the monarch’s representative in Ontario.

Both leaders would have been happy to see the term of the incumbent, Dr Herbert Alexander Bruce*, extended, but Hepburn wanted a Senate post for his defeated agriculture minister, Duncan McLean Marshall*, while King hoped to dissuade his provincial counterpart from closing the mansion. Hepburn was reluctant to go back on a campaign promise, however, and King guarded his appointment prerogatives. The outcome was another round of bitter recriminations. Bruce resigned and was replaced by a Toronto Liberal loyal to King, Albert Edward Matthews*; Chorley Park was closed and put up for sale. With the animosity still festering, the two Liberal chieftains clashed again over hydroelectricity sales to the United States. As a result of a negotiated settlement with the Quebec power companies, the province now had surplus power for sale and a ready market in New York State. The catch was that exports of hydroelectricity required federal approval. King’s government denied Ontario’s request, citing historical precedent. Hepburn was enraged and said so publicly.

He had already thrown down the gauntlet in a Toronto speech shortly after the Oshawa strike ended. “I am a Reformer,” he explained at that time. “But I am not a Mackenzie King Liberal any longer.” By 1938 Hepburn and King would each have liked to be rid of the other. Whereas King preferred to manoeuvre in the background while maintaining surface niceties, Hepburn was inclined to be brutally direct. Moreover, the Ontario premier was becoming bored with politics in his own province. One issue that raised some public hackles was his determination to introduce the mandatory pasteurization of milk. Convinced of the health risks, particularly from tuberculosis [see John Gunion Rutherford*], Hepburn held firm despite strong opposition from many of his own farm supporters, and the measure became law during the 1938 session.

This action revealed him at his best; the ongoing feud with Ottawa seemed to bring out his worst. Hepburn apparently viewed the royal commission on dominion–provincial relations [see Newton Wesley Rowell*; Joseph Sirois*], established by the federal government in 1937, as a tactic to outmanoeuvre Ontario and Quebec, the latter now led by his new friend and ally, Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis. In his statement to the commissioners in early May the following year, the Ontario premier stoutly opposed any centralization of powers or revenue in Ottawa. When the American president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, promoted a St Lawrence waterway during the dedication of the Thousand Islands Bridge at Ivy Lea in August, Hepburn, who had pointedly boycotted the event, quickly denounced the proposal as costly and unnecessary. He went on, in a truculent letter to King released to the public, to pledge Ontario’s continued resistance, “irrespective of any propaganda or squeeze play that might be concocted by you.” Intraparty conflict came to a head at a nomination meeting for federal transport minister Clarence Decatur Howe in Port Arthur (Thunder Bay) on 10 December, when King’s labour minister, Norman McLeod Rogers*, denounced an alleged conspiracy between Hepburn and Duplessis to topple the prime minister. Hepburn denied the charge but did not hide his contempt for federal policies.

The premier began 1939 with a trip to Australia to observe that country’s economic conditions and restore his own health. He returned in late February with a new concern: the pressing need for Canada to prepare for an impending world war. Not surprisingly, he detected in the federal government a distressing lack of urgency over this matter. His staunchest ally on the defence issue turned out to be George Drew, newly elected as leader of the Ontario Conservative Party. Their spirited clashes during debates in the legislature only seemed to lend more credence to those occasions when they declared a unanimity of purpose. In one such instance Hepburn moved, and Drew concurred, that “in the event of a War emergency the wealth and man power of Canada shall be mobilized … in defence of our free institutions.” Such non-partisan unity made both King and the federal Conservative leader, Robert James Manion*, nervous about possible ulterior motives. A brief truce between the two Liberal chieftains marked the visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth to Toronto in May, an occasion when the usually self-confident premier admitted to experiencing “a real attack of the jitters.”

After hostilities erupted in Europe in September, the Hepburn administration was quick to place the province on a wartime footing. A committee consisting of the premier, the lieutenant governor, and the opposition leader even journeyed to Ottawa early the following month to offer support and suggestions to King and his cabinet. As a conciliatory gesture, Hepburn withdrew his objections to the St Lawrence Seaway project. The federal ministers listened patiently, but both Hepburn and Drew chafed at the lack of concrete action. Rumours of a movement for a non-partisan union government were once again swirling about, while privately the premier toyed with the idea of resigning from office in order to pursue active service with the Canadian forces overseas.

Obsessed with the unfolding events of World War II, he longed for a larger role. King suspected that this ambition included taking on his own job as prime minister. When Drew spoke disparagingly in the Ontario legislature of the federal government’s timid leadership, Hepburn could not resist temptation. On 18 Jan. 1940, without consulting either cabinet or caucus, he moved a resolution “regretting that the Federal Government at Ottawa has made so little effort to prosecute Canada’s duty in the war in the vigorous manner the people of Canada desire to see.” It passed by a vote of 44 to 10, but the premier had split his own party. Ten brave backbenchers voted against him, while another 22 abstained, to avoid condemning their federal counterparts. Far from damaging the prime minister, Hepburn’s impetuous motion gave King grounds to call a snap election for 26 March, which the Liberals won decisively. Now it was Hepburn whose grip on the party in Ontario came into question. Harry Nixon, his trusted lieutenant, resigned from cabinet for a brief period, but Hepburn was able to coax him back. Nixon pointedly turned up on the platform at a King rally in Toronto on 14 March, and the premier’s outspoken criticism of the federal leader was muted, at least for a time. Another breakdown in his health sent him to a sanitarium in Battle Creek, Mich., for treatment of bronchial pneumonia. He returned in August much rejuvenated but with less stomach for partisan politics.

An invitation from King to attend a dominion–provincial conference in Ottawa in mid January 1941 soon raised Hepburn’s spirits. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss the report of the Rowell–Sirois commission, which had recommended a major overhaul of federal and provincial powers. In return for unfettered access to personal and corporate income taxes and succession duties, the federal government would assume all provincial debt, take over responsibility for unemployment relief, and allocate equalization grants to the provinces. In extending the invitation, King observed, “The Report commends itself strongly to our judgment.” When the conference opened, Hepburn quickly assumed the mantle of chief defender of provincial rights. He ridiculed the report as the “product of the minds of three professors and a Winnipeg newspaper man” and deplored the idea that “we should be fiddling while London is burning.” His most serious objection, however, was a substantive one: acceptance of the report would constitute “a surrender to a central authority of rights and privileges granted by the British North America Act.” Joined by premiers William Aberhart* of Alberta and Thomas Dufferin Pattullo of British Columbia, Hepburn stopped the conference in its tracks; the three provincial leaders were willing to discuss how the provinces could aid the war effort, but only if the agenda was not tied to the Rowell–Sirois report. King feared that the Ontario premier would call an election on provincial rights, and had he done so that spring, Hepburn might well have won. He was still master of the provincial scene, as witnessed by the ovation he received from his backbenchers when he brought in yet another budget surplus in March. Nixon, among others, urged him to go to the people, but Hepburn delayed, convinced that it was not appropriate to hold an election in wartime. Privately, he was still lobbying for a service position overseas; to his dismay, none was forthcoming.

In early 1942 King once again lifted Hepburn out of the doldrums. The federal throne speech promised Canadians an opportunity to release the Liberal government from its commitment not to introduce conscription for overseas service. The Ontario premier was outraged and denounced the plebiscite as “one of the most dastardly, contemptible and cowardly things ever perpetrated on a … country by any Government.” He offered his support to an old adversary, Arthur Meighen, who was once again leader of the federal Conservatives and running in a by-election in York South, and he also campaigned against King’s new labour minister, Humphrey Mitchell*, in Welland. Hepburn’s own cabinet was split, with Conant declaring that Meighen’s defeat would be a tragedy and Nixon claiming that his election would be a “national calamity.” Hepburn’s intervention counted for little; Meighen was defeated and Mitchell elected. Nevertheless, the premier’s hold on the provincial party remained firm, in spite of an attempt by Arthur Roebuck to force a leadership convention.

The main business of the legislative session that opened in February was to ratify an agreement by which personal and corporate taxation was transferred to Ottawa for the duration of the war, in return for federal grants. Though still master in his domain, Hepburn agreed with Tory member Leopold Macaulay that this decision had reduced Queen’s Park to a “glorified county council.” So bored had the premier become with his diminished role that he even privately offered to step aside and let the former lieutenant governor, Herbert Bruce, now a member of parliament, head a coalition government in the province. Bruce declined, but the incident demonstrates Hepburn’s increasingly erratic behaviour. His summer speaking tour included a new cause: that the nationwide ban on the Communist Party of Canada be lifted, now that the Soviet Union had become an indispensable ally. In the interests of a united war effort, he was prepared to work with these former adversaries. The premier’s health remained a problem, and his wife’s contraction of scarlet fever and his mother’s bout of cancer were added concerns. It nevertheless came as a shock when, on 21 October, Hepburn suddenly resigned as premier.

The unpredictable Liberal leader had designated the attorney general, Gordon Conant, as his successor. The lack of consultation with party colleagues did not sit well with Nixon, and he angrily withdrew from cabinet. Hepburn, who had agreed to stay on as provincial treasurer, rallied the rest of the caucus behind Conant for the upcoming legislative session with a promise that a leadership convention would be held at its conclusion. But he could not escape controversy, and when his unrelenting attacks upon the federal government included the charge that it was using “Hitler’s Nazi tactics,” the new premier had had enough. On 28 February Conant accepted the resignation of his former boss from cabinet, which had been held in abeyance since October. This action prompted Hepburn to lash out at the “Quisling government” in Ontario. Speculation mounted that he might attempt, in dramatic fashion, to succeed himself, but he was not present at the convention in April 1943, which chose Nixon as the new provincial leader. In the ensuing election campaign, Nixon sought to defend the Liberal record against two rejuvenated parties, George Drew’s Conservatives on the right and the resurgent CCF under Edward Bigelow Jolliffe* on the left. His plodding style on the hustings proved no match for these more eloquent adversaries, however, and on 4 August his party won just 15 seats, compared with 38 for the Tories and 34 for the CCF. One of the surviving Grit seats was held by Hepburn, who had run as an independent Liberal in Elgin, just as he had done in his first political race in 1925.

Mitch did not rejoin the Liberal caucus for over a year. When he did, Premier Drew had once more become his political enemy, while Hepburn, apparently untroubled by his inconsistency, now considered Prime Minister King an ally. The leading issue was family allowances; when Drew denounced them as a thinly disguised bribe to Quebec, Hepburn sprang to the defence of the federal initiative. At this sign of renewed vigour from their former chieftain, his provincial colleagues laid out the welcome mat for his return. Nixon himself moved that Hepburn become party house leader. In the legislative assembly he faced a much different situation from when he had been premier. Drew headed a minority Conservative government, and Jolliffe’s CCF formed the official opposition. Nonetheless, a rejuvenated Hepburn was soon plotting the downfall of the Tory administration, a feat he achieved by supporting a CCF no-confidence motion in the spring of 1945. Full of self-assurance, he launched his campaign in Windsor by unveiling a progressive Liberal platform. But this election was not to be 1934 over again. His party lacked funds, the organization had atrophied, and competitive candidates were hard to find. Drew successfully polarized the contest as a choice between free-enterprise Conservatives and the socialist CCF. Though large crowds came out to hear Hepburn, not nearly enough Ontarians voted for his fellow Liberals. On 4 June only 14 were elected, compared with 66 Conservatives. It was small consolation that the CCF, with 8, had fared even worse. Sadly, after five consecutive victories in federal and provincial contests, Hepburn was rejected by the voters of Elgin, soundly defeated on his home turf by a popular Tory, Fletcher Stewart Thomas. Mitch’s political career was abruptly over. He was 48.

Though disappointed, he received the election results with grace. “The people have spoken,” he responded, “and I accept their verdict.” As for the future, Hepburn stated that he would be returning to his farm “to listen to the grass grow.” Many times in the previous decade he had threatened to resign and go back to Bannockburn, his property in Elgin County, named after a historic battlefield in Scotland. Overseeing the thousand-acre enterprise was certainly a full-time job, particularly after he replaced the manager with himself. Despite the occasional rumour, he would never return to active politics. The candle of his political career had been extinguished on 4 June 1945. He was still a comparatively young man of 56 when his health, never robust, gave out for the last time. Hepburn died in his sleep, on the farm where he had been born, on 5 Jan. 1953. His funeral at Knox Presbyterian Church in St Thomas was attended by five Ontario premiers, past and present. Doubtless they agreed with the eulogist, the Reverend Harry Scott Rodney, who observed: “You met him, you shook hands with him, you were warmed by his famous smile, and you heard him say, ‘I’m Mitch Hepburn’; and in a few minutes you were calling him Mitch, and you liked it, and you felt you had always known him.”

Hepburn’s political career is a conundrum. A youthful prodigy in politics, he was an mp by 30, the leader of a political party at 34, and premier of Ontario before his 38th birthday. Conversely, he voluntarily resigned at 46 and was completely washed-up at 48. Like a shooting star, he appeared suddenly, burned very brightly, and then was gone. After he was chosen leader of the Ontario Liberals, Hepburn had set the benchmark for any assessment of his career in politics: “I am going to do my best,” he promised. “I am going to make some contribution to the welfare of this Province. I hope when my span is over on this earth it will be better than when I came in.”

Certainly, he brought improvements to the health of Ontarians through mandatory pasteurization of milk, better care for the mentally ill, and the construction of new hospitals. Progressive reforms in education resulted from his choice of Queen’s University historian Duncan McArthur*, first as deputy minister in 1934 and then as minister in 1940. For all Hepburn’s anti-CIO rhetoric, labour laws were significantly improved in favour of workers during his time in office. When legislation to equalize tax revenues for Catholic schools proved divisive, he quietly increased provincial grants to achieve the same purpose. Under his stewardship, the economy regained the ground it had lost in the early 1930s, and Ontario’s mines, mills, factories, farms, and offices were humming again a decade later. Not all the recovery was the work of his government, but as provincial treasurer, Hepburn produced budgetary surpluses while encouraging growth through highway construction, prudent hydroelectricity management, and selective support for resource industries. Along the way the civil service was streamlined, the judiciary restructured, and the scope of social services broadened, even as the province assumed some costs from the cash-strapped municipalities. Hepburn’s vigilance in collecting succession duties from the estates of the wealthy, while instituting a progressive personal and corporate income-tax scheme, did not endear him to the elite, but it laid the basis for the post-war Ontario model of progress with stability. His stout defence of provincial autonomy, in the face of centralizing pressure from Ottawa, safeguarded a balanced federation that could accommodate the centripetal forces of the coming decades. It was, if not an outstanding record, certainly a creditable one for the times.

“I am just a human being like yourselves,” Hepburn had stated in the midst of the 1937 campaign. “If I have made mistakes they have been mistakes of the heart.” Would that it were so, but, alas, most of his blunders were the logical outcome of the flaws in his character. An instinctive populist who railed against the condescension of those who lorded it over the little guy, he failed to appreciate how quickly he himself took on the airs of a big shot. Loyal to his friends, he was ruthlessly vindictive towards those he felt had crossed him. Blessed with boundless energy, an optimistic spirit, and a keen wit, he persisted in the raunchy bachelor lifestyle of his youth long after his medical record showed conclusively that it was unsustainable. Many of his faults came together in the prolonged feud with Mackenzie King. While there was blame on both sides, the brutal fact is that the federal leader used the ongoing conflict to his ultimate political advantage, while his provincial counterpart allowed it to destroy his career. As for the party, the federal Liberals in Ontario continued to compete successfully, but their provincial counterparts sank back into the chronic state of weakness from which Hepburn had rescued them. That frailty dated back to the early 1900s, but his two terms in office did not end it. Hepburn’s inability to put the party on a stronger, more durable footing would prove to be one of his greatest failures.

From a purely political perspective, his electoral triumphs in 1934 and 1937 were extraordinary. He was the only Ontario Liberal chieftain between 1905 and 1985 to lead his forces to victory, and he did so twice, each time with a solid majority. These landmark successes are explained not just by his charismatic platform style, although that was a factor. They also resulted from the creation of a stellar party organization, fuelled by ample financial resources from economic interests convinced that they would thrive in a province led by Hepburn. He was able to defuse two previously divisive issues – the sale of alcoholic beverages and the funding of Catholic schools – in such a way that they did not destroy Liberal unity or distract the voters from supporting his candidates. Hepburn also mobilized public discontent, first against the discredited Tory elite in 1934 and then against alleged foreign and Communist union agitators in 1937. Unfortunately for the party, he was not able to bequeath these winning conditions to those who followed. The decline in his physical health and emotional stability, coupled with the erratic nature of his retirement from the party leadership, proved fatal to the Liberals’ electoral prospects in the 1940s. Yet such was his impact on provincial politics that no truly capable successor would be found to fill his shoes for several decades. He was one of a kind, and while the party he led reaped the rewards of his victories, it also suffered long-term damage from his eventual downfall.

In the end we must conclude that Mitch Hepburn, in spite of his flaws and unfulfilled potential, did leave Ontario a better place as a result of his time in public office. And certainly it became a duller one without the mercurial politician once known as the “boy from Yarmouth” occupying centre stage. Leaders with personalities as contradictory as his – happy warrior one day, vindictive bully the next – have rarely appeared in the normally staid world of Ontario politics. His ebullient style was a bracing tonic for the desperation felt by many during the hard times of the 1930s. By the middle of the following decade, however, the province was returning to prosperity, and the courtly patrician, Colonel George Drew, better epitomized the hopes of the increasingly urbanized population. Hepburn, the colourful onion farmer from Elgin County, had served his purpose, and it was time for Ontario to move on.

The Mitchell F. Hepburn fonds (F 10) is held by the Arch. of Ont. in Toronto. Other pertinent collections there include the papers of two prominent opponents – Howard Ferguson (F 8) and George Henry (F 9) – and Hepburn’s cabinet colleagues Gordon Conant (F 12), Thomas Baker McQuesten* (F 39), and Arthur Roebuck (F 45). The papers of his long-time arch foe, Mackenzie King (R10383-0-6), and another antagonist, George Drew (R5606-0-9), are at Library and Arch. Can. in Ottawa. Those of Herbert Bruce, Ontario’s lieutenant governor during Hepburn’s first term in office, are in the Queen’s Univ. Arch. in Kingston, Ont. The Canadian annual rev. of public affairs (Toronto), edited by John Castell Hopkins*, is a valuable source for the years 1926/27 to 1937/38. Among daily newspapers useful to this study, the Times-Journal of St Thomas, Ont., originated in Hepburn’s home riding, while others of particular value include the Toronto Globe and Mail, its two predecessors, the Globe and the Mail and Empire, and the Toronto Daily Star.

There are two full-length biographies of Hepburn: Neil McKenty, Mitch Hepburn (Toronto, 1967) and J. T. Saywell, ‘Just call me Mitch’: the life of Mitchell F. Hepburn (Toronto, 1991). Reference should also be made to R. MacG. Dawson and H. B. Neatby, William Lyon Mackenzie King: a political biography (3v., Toronto, 1958–76), 3 (The prism of unity, 1932–1939), and J. W. Pickersgill and D. F. Forster, The Mackenzie King record (4v., Toronto, 1960–70), 1 (1939–1944). The lieutenant governor’s view of the Chorley Park episode is covered in his memoirs: H. A. Bruce, Varied operations: an autobiography (Toronto, 1958).

Volumes 15 and 18 of the Canadian centenary ser. supply a rich pan-Canadian context for Hepburn’s public life: J. H. Thompson and Allen Seager, Canada, 1922–1939: decades of discord (Toronto, 1985) and D. [G.] Creighton, The forked road: Canada, 1939–1957 (Toronto, 1976). A helpful survey history of post-confederation Ontario is provided in Joseph Schull, Ontario since 1867 (Toronto, 1978). Hepburn’s tumultuous relationship with the federal government is well handled in Christopher Armstrong, The politics of federalism: Ontario’s relations with the federal government, 1867–1942 (Toronto, 1981), while the impact of the resource industries on Ontario politics during his time is covered in H. V. Nelles, The politics of development: forests, mines & hydro-electric power in Ontario, 1849–1941 (Toronto, 1974). Further insight on the Hepburn–King feud can be found in J. L. Granatstein, Canada’s war: the politics of the Mackenzie King government, 1939–1945 (Toronto, 1975) and Reginald Whitaker, The government party: organizing and financing the Liberal Party of Canada, 1930–58 (Toronto, 1977).

Several journal articles are worth noting. Neil McKenty discusses Hepburn’s triumphant first campaign as Liberal leader in “Mitchell F. Hepburn and the Ontario election of 1934,” Canadian Hist. Rev. (Toronto), 45 (1964): 293–313. The impact of religious schools on the 1937 campaign is dealt with in R. [M. H.] Alway, “A ‘silent’ issue: Mitchell Hepburn, separate-school taxation and the Ontario election of 1937,” in Policy by other means: essays in honour of C. P. Stacey, ed. Michael Cross and Robert Bothwell (Toronto and Vancouver, 1972), 201–18. A thorough examination of the Chorley Park controversy can be found in Colin Read and Donald Forster, “‘Opera bouffe’: Mackenzie King, Mitch Hepburn, the appointment of the lieutenant-governor, and the closing of Government House, Toronto, 1937,” Ontario Hist. (Toronto), 69 (1977): 239–56. Alway analyses one of the key issues in the ongoing Ontario–Ottawa conflict of this era in “Hepburn, King, and the Rowell-Sirois Commission,” Canadian Hist. Rev., 48 (1967): 113–41. Thorough coverage of Hepburn’s role in the General Motors strike is provided by Irving Abella, “Oshawa 1937,” in On strike: six key labour struggles in Canada, 1919–1949, ed. Irving Abella (Toronto, 1974), 93–128. Finally, Neil McKenty summarizes Hepburn’s political and ideological views in “That Tory Hepburn,” in Profiles of a province: studies in the history of Ontario, ed. E. G. Firth (Toronto, 1967), 137–41.

Cite This Article

Larry A. Glassford, “HEPBURN, MITCHELL FREDERICK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hepburn_mitchell_frederick_18E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hepburn_mitchell_frederick_18E.html |

| Author of Article: | Larry A. Glassford |

| Title of Article: | HEPBURN, MITCHELL FREDERICK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2013 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |