Source: Link

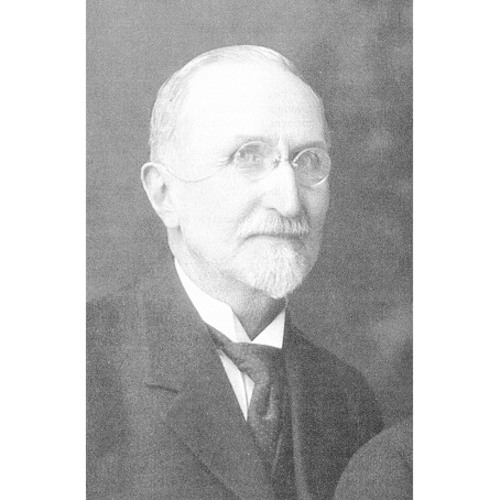

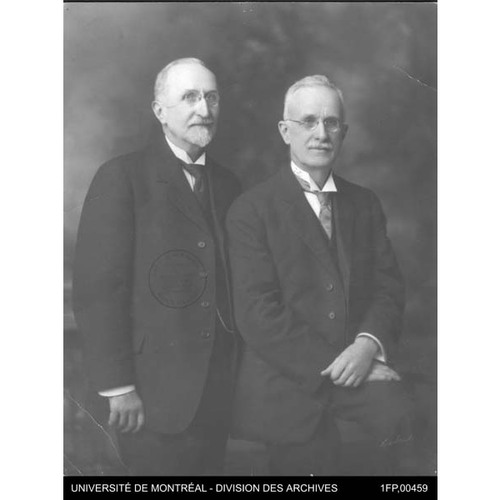

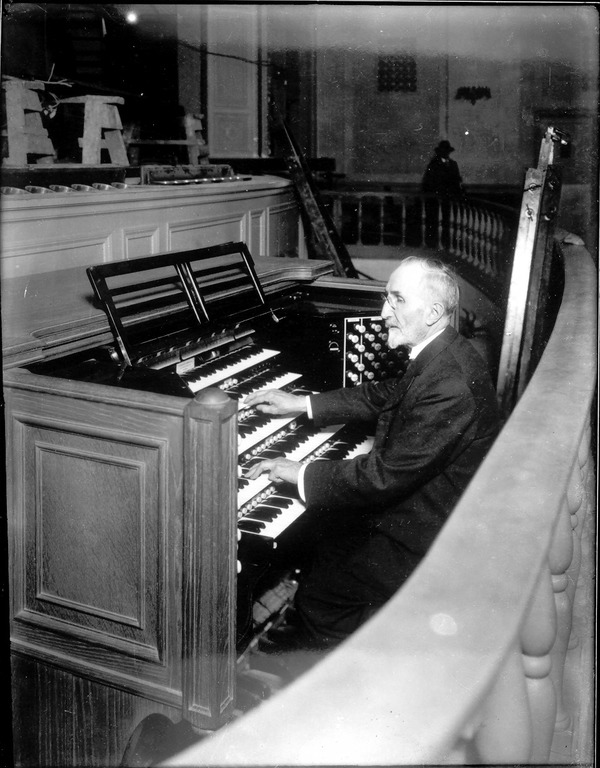

CASAVANT, CLAVER (baptized Joseph-Claver, he sometimes signed Claver and sometimes Joseph-Claver), organ builder and tuner, and businessman; b. 16 Sept. 1855 in Saint-Hyacinthe, Lower Canada, son of Joseph Casavant*, an organ builder, and Marie-Olive Sicard; m. 26 May 1880 Marie-Sophie-Évelina Papineau (d. 24 Jan. 1930), niece of Louis-Joseph Papineau*, at Sainte-Angélique (Papineauville), Que., and they had eight children, three of whom survived him; d. 10 Dec. 1933 in his native village and was buried there four days later in the crypt of the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe.

Claver Casavant studied at the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe from 1867 to 1871. He then learned the rudiments of organ building from Eusèbe Brodeur, who in 1866 had become the owner of the company belonging to his former employer, Claver’s father. When the senior Casavant died in 1874, Brodeur assumed the role of guardian of his two sons, Claver and Samuel, until Claver came of age.

In August 1878 Claver, then 22 years old and employed by Brodeur, set out for Europe on a work-study trip. His brother, Samuel, would join him the following year. This sojourn, which began in France and continued in Italy, Switzerland, the German empire, Belgium, and England, would have a profound effect on him, both personally and professionally. At that time Claver abandoned the idea of becoming a Jesuit and confirmed his desire to follow in his father’s footsteps as an organ builder. After frequent visits to the 1878 universal exposition in Paris, he worked from October as a salesman, labourer, and, most importantly, tuner for the organ factory of the brothers Eugène and John Abbey in Versailles. While the Abbey enterprise certainly did not have the reputation of Aristide Cavaillé-Coll’s company, it nevertheless had won a silver medal at the exhibition that year.

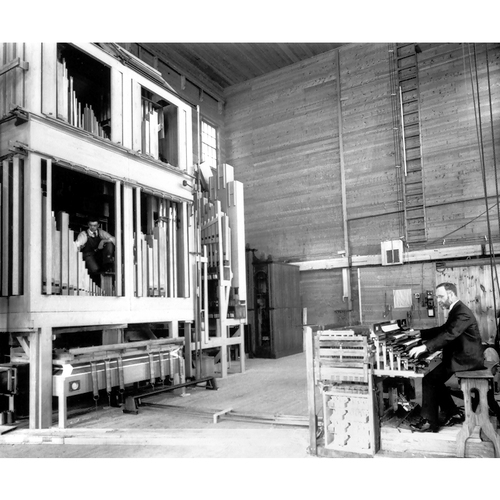

After returning to Saint-Hyacinthe in October 1879, Claver and Samuel founded Casavant Frères. For their first instruments, the Casavants incorporated European innovations in organ building, such as the concave pedalboard, the dual-action expression pedal, manuals set closer together, and the frein harmonique. The influence of the Abbey organ builders could be seen in the use of the concave pedalboard instead of the straight pedalboard and in the closeness of the manuals, two improvements that had earned the jury’s praise for the Abbeys at the 1878 universal exposition. Furthermore, their father, John Abbey, had invented the frein harmonique, a copper device placed at the opening of a pipe to regulate its tone more precisely and more quickly.

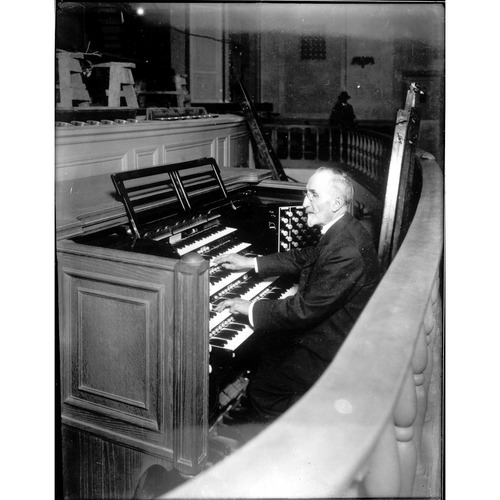

The first organ built by Casavant Frères, which had two manuals and 13 stops, was installed in the chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes in Montreal in 1880. In view of its favourable evaluation by 10 or so musicians, the firm was chosen over that of Eusèbe Brodeur to design the three-manual, 38-stop instrument for Saint-Hyacinthe’s cathedral, which it installed in 1885. The reputation of Casavant Frères was further enhanced by its creation of the organ for Notre-Dame church in Montreal, which was inaugurated in 1891. With four manuals and 81 stops, it was one of the most impressive organs in North America at that time and the envy of organ makers in France, who were building very few new instruments at the turn of the century, primarily because the country was becoming increasingly secularized.

The Casavant firm perfected the art of organ building, and several American and European makers adopted its innovations. In 1889 the physician and organist Salluste Duval* had taken out a patent in the United States for the adjustable-combination pedal, a device that enabled organists to program a set of stops in advance. This technology, improved by Duval in the workshops of Casavant Frères at the beginning of the 1880s, was then taken up, imitated, or improved by other builders. The company was also a world pioneer in the electrification of the organ. Its first instruments to employ electro-pneumatic action were installed in 1892 in Ottawa’s Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica and the church of Notre-Dame-du-Rosaire in Saint-Hyacinthe.

At the end of the 19th century, with competition becoming increasingly weak, the firm dominated the Canadian organ-manufacturing market. Beginning in 1895 it also started to export its instruments to the United States. To avoid high tariffs, it operated a branch plant in South Haven, Mich., from 1912 to 1918. The company’s fame in Europe was reinforced in 1923 when it had an electro-pneumatic organ delivered to the Paris residence of the American philanthropist and patron of the arts Florence Meyer Blumenthal and in 1930 when it won the grand prize at the International Exhibition: Colonial, Maritime, Flemish Art at Antwerp, Belgium.

In 1919 Casavant Frères had become a limited-liability company. Claver was made president and Samuel vice-president. Despite this change in status, Claver continued to be involved in product specifications and assumed responsibility for voicing, while Samuel carried out administrative tasks and research on organ mechanisms. That year the two brothers founded the Compagnie de Phonographes Casavant Limitée, which until 1926 produced various models of phonographs. The death of Samuel, one month after the stock-market crash of October 1929, coincided with the end of the stunning growth of Casavant Frères Limitée. The company had developed from 3 employees in 1880 to 38 in 1900, and then to 170 in 1911, and about 250 in 1929. That year it produced 55 organs, including one for the Royal York Hotel in Toronto, the first Canadian organ with five manuals.

Such expansion had entailed a great deal of travel for Claver, especially in Canada and the United States, to install and voice organs. He rarely travelled as a tourist. In 1905 he went to London with a delegation from the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association as an elected member of the executive committee of the Montreal branch. He refused to accompany his daughter Alice to Europe in 1932, instead choosing to turn over to the poor the money he would have spent on this pleasure trip. Indeed, he was a passionate and discreet philanthropist throughout his life. He contributed substantial sums, some to the destitute and some to organizations and institutions in his hometown, including the Sisters of the Presentation of Mary, the seminary, and the hospital.

Casavant agreed to run for mayor of Saint-Hyacinthe on 26 June 1920 at the insistence of a number of citizens. Throughout the campaign, one of his supporters was the Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe, an independent Roman Catholic weekly published by the Compagnie d’Imprimerie et de Comptabilités de Saint-Hyacinthe, of which Casavant would become president in 1923. Repelled by the combativeness that characterized an election campaign and lacking experience in municipal affairs, he was defeated on 12 July by the incumbent, Télesphore-Damien Bouchard*, who nevertheless won by only 45 votes.

A practising Catholic and a deeply religious man, Casavant attended mass every day at the seminary chapel. In 1925 Pope Pius XI named him a knight commander of the Order of St Gregory the Great in recognition of his Christian virtues, his religious spirit, his exemplary life, and his commitment and devotion to the Holy See.

Despite his reserved personality, Claver Casavant was a purposeful worker to the end of his life and, together with his brother, was able to manage one of the most important organ-building companies in the world. As of his death in 1933, the company had, since its founding in 1879, built 1,484 organs, the great majority of them installed in North America, but also in Europe, South America, Central America, Africa, and Asia. Claver was succeeded as president of Casavant Frères Limitée by Samuel’s son (Aristide, 1933–38) and then by the latter’s son-in-law (Frederic N. Oliver, 1938–63). Stephen Stoot was in charge of tasks related to artistic direction from 1933 to 1958.

The Great Depression had dealt a severe blow to Casavant Frères Limitée: in 1933 only 11 new organs left its workshops. To ensure the continuity of the business after Casavant’s death, its new directors supported initiatives that had been previously rejected or that ran counter to the philosophy of its founders, such as the manufacture of unit organs from 1936 and the creation of a furniture department in 1938. In the early 21st century, the organ-manufacturing company remains one of the greatest in the world and the oldest one functioning in Canada.

Arch. de Casavant Frères Limitée (Saint-Hyacinthe, Québec). BANQ-CAM, CE602-S1, 16 sept. 1855. Centre d’Hist. de Saint-Hyacinthe Inc., CH001; CH097; CH122; CH356. FD, Cathédrale Saint-Hyacinthe-le-Confesseur, Saint-Hyacinthe, 28 janv. 1930, 14 déc. 1933; Sainte-Angélique (Papineauville, Québec), 26 mai 1880. L’Action catholique (Québec), 11 déc. 1933. Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe, 9 août 1878; 9 juill. 1910; 29 juill. 1911; 27 juill. 1912; 3, 10 juill., 14 août 1920; 6 janv. 1923; 10, 17, 24 juill., 29 nov. 1929; 8, 15, 22 déc. 1933. Le Devoir, 11, 13 déc. 1933. La Minerve (Montréal), 15 août, 5, 7, 19, 24 sept. 1885. La Presse, 11, 12, 15 déc. 1933. Antoine Bouchard, “Casavant Frères: facteurs d’orgues depuis un siècle,” Forces (Montréal), no.2 (1967): 29–34. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). [Samuel Casavant], “Les débuts de la facture d’orgues au Canada,” La Musique (Québec), 3 (1921): 130–33; Un orgue canadien à Paris … (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1924). C.‑P. Choquette, Histoire de la ville de Saint-Hyacinthe (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1930). Gustave Chouquet, Exposition universelle internationale de 1878, à Paris, groupe II, classe 13: rapport sur les instruments de musique et les éditions musicales (Paris, 1880). Jeanne D’Aigle, L’histoire de Casavant Frères, 1880–1980 (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1989). Dictionnaire biographique de musiciens et un vocabulaire de termes musicaux (Lachine [Montréal], 1922), 54–55. Norbert Dufourcq, “Précisions historiques sur l’orgue électrique en France, au Canada, et aux États-Unis,” La Rev. musicale (Paris), 10 (1928–29), no.10: 41–51. F[rère] Élie [J.‑S.‑Z. Phaneuf], La famille Casavant (Montréal, 1914). Kallmann et al., Encyclopédie de la musique au Canada, 1: 526–29. Laurent Lapointe et al., Casavant Frères, 1879–1979 ([Saint-Hyacinthe], 1979). Victor Morin, I: In chordis et organo (fastes d’organiers); II: Mon clocher (causerie radiofusée) (Montréal, 1940). The organ: an encyclopedia, ed. D. E. Bush and Richard Kassel (New York, 2006). M.‑R. Sauvé, Joseph Casavant: le facteur d’orgues romantique (Montréal, 1995).

Cite This Article

Louis Brouillette, “CASAVANT, CLAVER (baptized Joseph-Claver),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/casavant_claver_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/casavant_claver_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Louis Brouillette |

| Title of Article: | CASAVANT, CLAVER (baptized Joseph-Claver) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |